A note on Rumi's cosmology

Rumi's approach to metaphysics is fundamentally essential. He prescinds from dry and technical phrases, and penetrates into the heart of his subject in the simplest manner.

To understand the relation of the World to its Creator, and to gain insight into the indefinite realms that exist between the material plane and the divine Presence, has been the chief aim of all traditional cosmologies. Unlike modern "cosmology" which still falls into the domain of "physicality" or the material plane, traditional cosmology explores levels of being beyond matter, beyond our immediate horizons.

In the words of Professor Nasr, traditional cosmology, whether Islamic, hermetic, kabalistic or otherwise "is like sacred art which, out of many possible forms chooses a certain number, in order to paint an icon with a definite and particular meaning, designed more for contemplation than for analysis."1 These various cosmologies have been developed and further elaborated by mystics and metaphysicians, philosophers and scientists.

In the case of Islam, for example, its cosmology is derived fundamentally from the Quran, and philosophers such as Ibn Sina and Mulla Sadra have sought to establish their cosmological views based on Quranic principles. In the Quran we are told of seven earths and seven heavens, of the Divine Throne ('arsh) and Pedestal (kursi), and the cosmic Mountain of Qaf. On the other hand, philosophers such as Farabi and Avicenna, when discussing the emanation of Creation from Being, have designated ten intelligences ('uqul-i ashare), which came to be known in the Islamic world as the “theory of mediation” (nazariye-i vasaet). This theory dominated the Islamic intellectual scene until the 7th century AH, and most philosophers and mystics – with the exception of al-Qazzali and Fakhr al-Din Razi – were in agreement with this thesis.

This theory states that from unity only unity can arise (ex uno non fit nisi unum). God, who is Absolute Unity intrinsically, cannot effuse anything less than unity. The origin of this dictum is unknown; al-Farabi attributes it to Aristotle, whereas Averroes states that it had originated from Plato and Themistios, making no mention of Aristotle. Despite the unknown origin of this doctrine, however, the majority of philosophers, theologians and metaphysicians throughout history viewed it to be axiomatic.

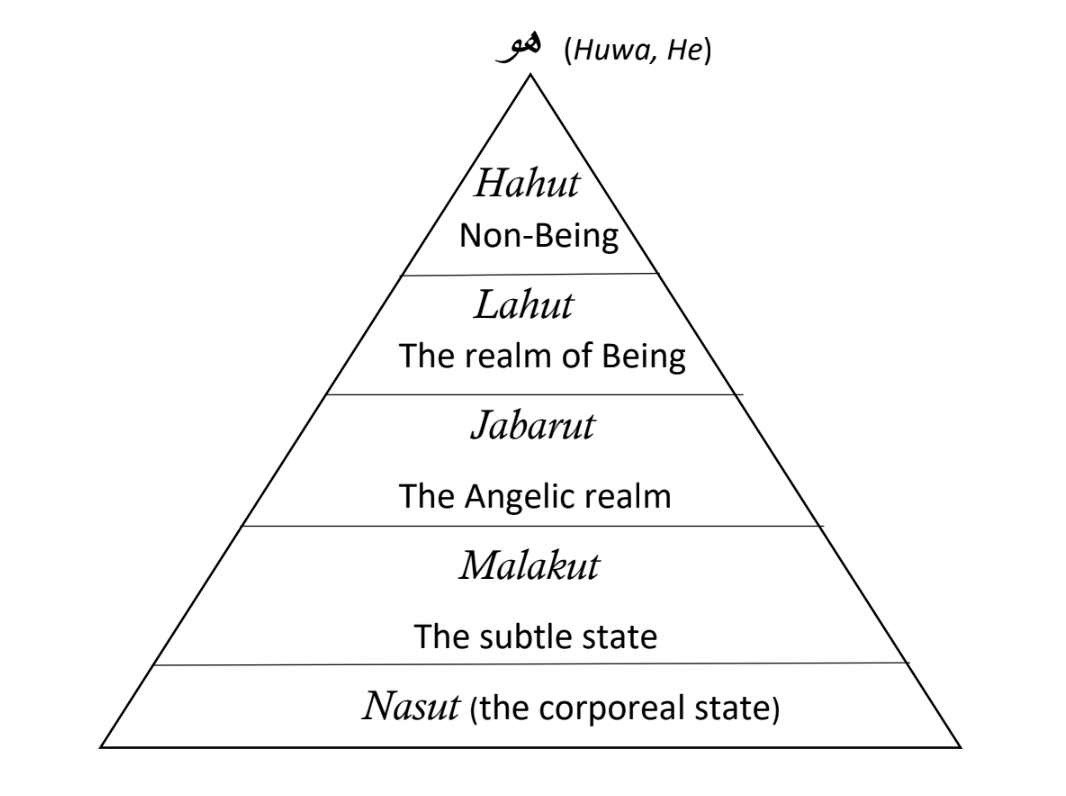

Another form of cosmology was also developed in Sufism, the mystical aspect of Islam. The Sufis’ cosmological doctrine differed from the philosophers not so much in structure, but in viewpoint. The multiple states of being in Sufism came to be known as "Hazarat-i khams" or the Five Divine Presences. This viewpoint can be envisaged symbolically in the form of five concentric circles. At the very center of which stands the absolute Essence of God, and with every centrifugal circle the level of reality becomes more "inferior" and "opaque" until we reach the realm of corporeality, which is located at the outermost periphery and, compared to other states, contains the highest level of density. The Five Divine Presences are as follows:

- Nasut: The human or corporeal realm, the domain of sensorial existence, conditioned by time and space; the realm of relativity and the lowest level of reality, in which God is most absent or has the least presence.

- Malakut: the animistic or subtle realm, or the "realm of royalty" because it dominates the corporeal world.

- Jabartut: "Heaven" or the "realm of power," which can also be designated as the formless, intellectual and angelic realm.

- Lahut: A derivative of "Allah," meaning the "Divine" realm, incorporating the divine names and qualities (asma-i ilahi); other names are the “realm of commandment” (alam-i amr), the "Unseen" (alam-i qayb).

- Hahut: Derivative from "Huwa" (وھ), "He"; meaning "Aseity," "Ipseity," or "Quiddity," the supreme Principle and Divine Essence.

In the technical language of perennial philosophy, the above terms are designated as the following in ascending order: (1) the gross or material state; (2) the subtle or "spiritual" realm; (3) formless and supra-formal Manifestation, or the paradisiac or angelic realm; (4) Being, which is the ontological Principle; (5) Non-being, or Beyond Being, which has also been called the "desolate Godhead," "dark mist," "Unconsciousness," or "immanent negativity"; this state is purely unconditioned and unmanifest, undetermined and by no means intelligible to human cognition.

But Rumi's cosmology does not follow the theory of mediation of philosophers nor the Five Divine Presences of the Sufis – at least on the surface. There is every reason to believe that Rumi had been familiar with the aforesaid theories and other philosophical doctrines of his time; but due to the dearth of material dealing with these concepts in his opus, we may infer that his cosmological views differed from his philosophical peers. In the outset, however, we ought to mention that the two major themes to which Rumi is dedicated are theology and anthropology; in fact, this was the prevalent view amongst Muslim mystics until the 7AH, who are known as the mystics of the first tradition. For these people the knowledge of God and the Self was of primary importance and the summum bonum. It was only after this period that cosmology became incorporated into their worldview, and thus became an important concern.

Rumi in a sense stands between these two "traditions," with an inclination towards the first; he is more in the tradition of Socrates, and stands with the preëminence of Self-knowledge rather than knowledge of the Cosmos. For this reason, there are only a few instances in which he makes a direct reference to the gradation of being and the hierarchical structure of the world.

When expounding his cosmology, Rumi refrains from using the technical vocabulary of theoretical Sufism, even though he is evidently familiar with them. Here we observe a drastic difference between the school of Rumi and other Sufi mystics such as Ibn Arabi, who was contemporary to Mawlana. Such figures as Ibn Arabi and Jili made extensive use of technical phraseology, which are often very obscure and almost unintelligible to the average reader. Rumi, however, would cloak his message in the simplest terms, and in a manner analogous to the Quran, heavily draws upon analogies and parables rather than technical terminologies. His language of discourse is non-technical, more "direct" and highly tangible. This of course does not make his content easier to grasp or less precise, on the contrary, it requires from the reader a more direct vision, an ability to "see" without words:

O God, do reveal to the Soul that station

in which speech is growing without words. (I, 3095)

A Sufi master (whose name I have forgotten) had said that a chapter of Ibn Arabi is contained in a page of Rumi's Mathnawi. This claim may sound slightly audacious, but for those familiar with Rumi's language of discourse this statement is not altogether incorrect. Rumi's approach to metaphysic is fundamentally essential, meaning that he prescinds from dry forms of elucidation and technical phrases, and penetrates into the heart of his subject in the simplest manner. Another reason that explains Rumi’s simple language is the following. Rumi was often preaching to the common-people; his circle of students, aside from a few advanced pupils such as Hussam al-Din, was comprised of ordinary persons, salesmen and laymen who had genuine interest in divine knowledge (Irfan) but had no proper training in theoretical Sufism. Finally, we should remember that Rumi never composed a treatise specifically dealing with Sufism or metaphysics, but his exposition of these subjects is hidden under the veils of his tails and analogies.

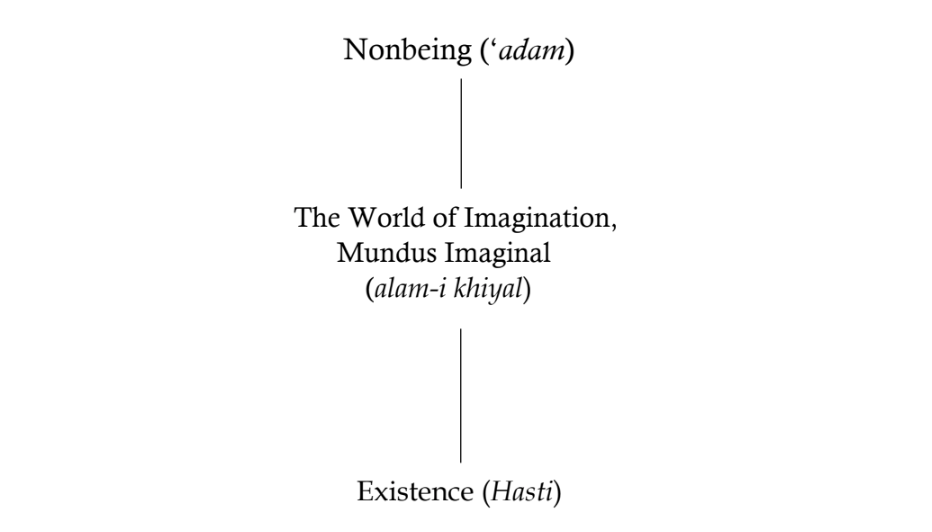

Be that as it may, based on Rumi's cosmological verses, we may illustrate his view of the Cosmos as the following:

Nonbeing ('adam)

We have already dealt with Rumi’s conception of “nonbeing” in our article, The Sea of Nonexistence. To avoid repetition, we refer to the reader to that article. Save it to say that Rumi views nonbeing (‘adam) to be the Fons Vitae, the Source from which being, existence, imagination, creation, spring forth. Nonexistence here should not to be understood in negative terms, that is, a sort of deficiency. God Himself is No Thing; that is, no thing amongst others. In other words, whatever we say of God is not God, but one of His effects, according to the Angelic Doctor. Observe the following verses:

Nonexistence is God's factory

from which he continually brings out gifts.

(V, 1017-25)

Since you have heard the description

of the sea of non-existence

continually seek to stand upon this sea.

For the origin of God's workshop is that non-existence;

it is void, traceless, and empty.

All the masters seek non-existence,

necessarily God who is the Master of masters,

His workshop is non-existence and naught.

Wherever this non-existence is greater,

in there is God's work and workshop more manifest.

Since non-existence is the highest station,

the dervishes have outstripped all.

(VI, 1466-71)

The World of Imagination (alam-i khiyal)

Rumi’s usage of the term khiyal, or imagination, is twofold: firstly, by khiyal he refers to the ordinary human function which forms mental conceptions and images by means of sensory perception. Khiyal according to Muslim philosophers, is one of the five innate faculties of comprehension, namely: Synaisthesis (hiss-i mushtarak)2, imagination, faculty of apprehension (wahm), reason, and memory.

The Muslim philosopher-metaphysician Suhrawardi says:

The innate senses are also five: first is common sense, and that is a faculty in which all perceptions gather...second is the faculty of imagination, and that is the storage of synaistheis in which all mental images remain...third is faculty of apprehension (wahm) and that is a faculty which conjectures about the imperceptible by means of the perceptible...fourth is the imaginative faculty (mutikhayille), and that is the faculty which compounds and categorizes images and decisions...but since this is done by the intellect we call it the reasoning faculty (mutifakkire)...fifth is the faculty of memory, which is a power located in the concave of the brain, serving as a storage for the faculty of comprehension.

Khiyal is therefore a faculty used for comprehension and attaining knowledge. In the view of the Platonic philosophers, the lowest level of knowledge is acquired by the means imagination.

An essential characteristic of imagination or fantasy, according to Rumi, is that it is and is not. In the first story of the Mathnawi, when the divine physician approaches the king in his sleep, Rumi says,

From afar he came

like the crescent moon,

it was existing and nonexisting

in the shape of a phantasy.

The "shape of a phantasy" is indeed peculiar. On the one hand, the mental images formed by the mind have a reality, for we “perceive” them; on the other, they are nonexistent for having no external reality. Rumi designates the term khiyal to all trivial and unimportant matters.

In the soul, phantasy is as naught,

yet behold a world turning on phantasy.

Their peace and war result from a phantasy,

their pride and shame spring from a phantasy.

(I, 70-71)

From this viewpoint, the perceptible world is reduced virtually into phantasy – a "non-existing existent." In his Discourses, Rumi writes:

The world subsists on imagination. And you call this world “reality” because you perceive it. But those meanings of which this world is subordinate, you call phantasy – it is the other way round. In fact, this world is fantasy and that Essence has created a hundred of these worlds and dissolved and destroyed, and again created a new world.

The second meaning of Khiyal as mentioned by Rumi, designates the vast world of Imagination which occupies a state in the hierarchical structure of being. This realm is by no means similar to our modern understanding of the term, which denotes representations of the mind. A sound description of this realm has been given to us by the theologian, Henry Corbin:

Between the world of pure spiritual Lights (Luces victoriales, the world of the “Mothers” in the terminology of Ishraq) and the sensory universe, at the

boundary of the ninth Sphere (the Sphere of Spheres) there opens a mundus

imaginalis which is a concrete spiritual world of archetype-Figures, apparitional Forms, Angeles of species and of individuals; by philosophical dialectics its necessity is deduced and its plane situated; vision of it in actuality is vouchsafed to the visionary apperception of the Active Imagination. The essential connection in Sohrevardi which leads from philosophical speculation to a metaphysics of ecstasy also establishes the connection between the angelology of this new-Zoroastrian Platonism and the idea of mundus imaginal. This, Sohrevardi declares, is the world to which the ancient Sages alluded when they affirmed that beyond the sensory world there exists another universe with a contour and dimensions and extension in a space, although these are not comparable with the shape and spatiality as we perceive them in the world of physical bodies. It is the “eighth” keshvar, the mystical Earth of Hurqalya with emerald cities; it is situated on the summit of the cosmic mountain, which the traditions handed down in Islam call the mountain of Qaf.

(The Man of Light in Iranian Sufism [1971], pp. 42-3).

Following the terminology of Corbin, we hence call this realm the Imaginal. According to Corbin, the usage of the terms imaginary or imagination is inappropriate when defining this realm, for imaginary in modern connotation signifies something unreal, or superstitious; whereas the Imaginal, or the "eighth climate," has an intrinsic reality and can be conceived with the organ of imaginative consciousness, or cognitive Imagination.

I return now to Rumi. Speaking about Rumi's view of the Imaginal is difficult due to the limited verses dealing with this realm. However, there are three possible ways of dealing with Rumi’s view on this topic: (1) the Imaginal is situated "below" non-being, and “above” the sensory universe; in other words, the Imaginal functions as an inter-world (barzakh) between nonbeing and the sensorial world; (2) the Imaginal springs from nonbeing; (3) whatever that is perceptible for human beings in the sensorial world, from dreams and phantasies, stem from the Imaginal. Again, in his discourses Rumi says:

The Imaginal, with respect to the world of senses and perceptions, is wider. For all things that can be perceived are issued from the Imaginal, and the Imaginal is more constrained with respect to the realm from which it is issued [namely, nonbeing].

There is only one reference to the gradation of being in the Mathnawi:

O God, do Thou reveal to the soul that station

wherein speech is growing without letters.

That the pure spirit may fly headlong towards the

far stretching expanses of nonbeing.

An expanse very wide and spacious

from which this phantasy and being of ours is fed.

The realm of phantasies is narrower than nonbeing,

since phantasy is the cause of pain.

Existence, again, is narrower than the realm of phantasies,

hence in it moons become like the moon that has waned.

Again, the existence of the world of sense and color is narrower,

for it is a narrow prison.

The cause of narrowness is composition and number,

the senses are moving towards composition.

The levels of being are also mentioned in book four of the Mathnawi (V. 3692-93). Here, Rumi mentions the Quranic doctrine that views Reality through a bipartite perspective. In the Quran we read, "His is the Creation and his is the Command." Command ('amr), according to Muslim philosophers, designates the world of detached spiritual abstractions (mujarradat); Creation ('khalq), refers to the world perceived by the five senses. According to Mulla Sadra, God has created many worlds which fall into one of the two domains mentioned. For example, the body comes from Creation, whereas the spirit is from the world of Command. Now, In Rumi's words:

The world of Creation is endowed with quarters and directions, but the world of divine Command and Attributes is without direction.

Know that the world of Command is without direction, of necessity the Commander is even more without direction.

The Sensorial World (dunya)

If we envisage the gradation of being vertically, then the world of matter would occupy the lowest position in the vertical axis. This is due to the opaqueness of matter. Here, the density of existence is felt; the subject in this level of reality is fragmented, and separated from his or her Source; he is thrown into the bondage of time and space; he is now in exile.

Ibn Sina, the eminent Muslim philosopher, makes a connection between the nine spheres and ten intelligences, and places the world of matter below the Sphere of Moon. According to Ibn Sina, the Sphere of Spheres, or the Empyrean (falak al-aflak), has the greatest degree of abstraction and tenuity, and as we progress downwards to more inferior spheres, abstraction decreases and density increases, until we reach the sensorial world which according to Ibn Sina, is "dominated by density and opaqueness," and has the least amount of abstraction.

Now, in Rumi's view the world that we live in is a dream, or in other terms, a shadow. It is a dream for nothing is permanent, and a shadow for whatever we acquire is fleeting, transient, and incapable of satisfying us deeply. In his writings, Rumi often refers to the world as a "dream" (khab), "fantasy" (khiyal), "prison" (zendan), "mirage" (sarab), "well" (chah), "shadow" (sayeh), and a "false dawn" (subh-i kazeb). For example, he explicitly tells us that "this world is a dream" and if we happen to lose something in a dream it should not bother us. Another place he states that the foundation of the world is based on fantasy, and imagination is the sole drive of our activities. He refers to the world as a mirage and compares us to thirsty people seeking water in the wrong place. Again, he compares the world to a well, and says that inside this well there are, what he so eloquently termed, "optical inversions" (in'ikasat-i nazar), which prevent us from seeing things as they truly are. The theme of inversion is central in Rumi's doctrine. This "optical inversion," or as a modern European writer has termed, "intellectual myopia," causes one to mistake one thing with another; the least of which is to make stone with gold.

All these references reflect how Rumi saw the nature of the world to be deceptive, illusory, and unreal. Now, does this mean that we should not take the world seriously and regard it as without value? Never does Rumi suggest this. In fact, following the principle of analogy and correspondence, he regards the world to be a symbolic reflection of a higher order of existence; when Sufis and other metaphysicians talk about the unreality of the world, it does not follow that it is mere "illusion," and has no reality whatever; on the contrary, the world inasmuch as it exists and insofar as it is a manifestation of the Divine Self into a lower domain of reality, has a relative reality in its own right, otherwise it would not exist. To use the terminology of the Advaita Vedanta school, the world is Maya, which is translated by such authorities like Ananda Coomaraswamy as "Magic" and "Art." The world, therefore, is God’s artifice. And since every creation implies a separation from its creator, the world, to the degree of its "separation" from God, is necessarily imperfect; in other words, the world is not true Reality, but only Atman, or the Divine and true "Self" underlying the ego and all manifestation, can be said to be real.

In Sufi metaphysics, too, the world is considered to be a hijab (veil)3. And according to a tradition by the prophet, there are seventy thousand veils of light and darkness that separate us form the Divine Presence. The path to God is therefore long and arduous and requires an impeccable discipline and an unwavering dedication. The journey of the "alone to the Alone" is no other than a constant Jihad; a tearing apart the veils of ignorance that separate us from the One. The spiritual Traveler, in the beginning of his or her Wayfaring, regards all multiplicity to be real and thinks of the world to be self-subsistent. However, when the shell of multiplicity is shattered and the veils of ignorance are torn, the traveler is then able to see the One in the many and the many in the One. In other words, they will perceive the Unity underlying the World and the dependence of all multiplicity on an intrinsic connectedness.

To deal with all the verses pertaining to the nature of the World in Rumi's work falls beyond the scope of this essay. However, we will mention a few verses that bear upon the nature of the Universe. Here we only make reference to Rumi’s conception of the world as a prison.

The World as a Prison

Rumi has often compared the World to a prison, and has sought to liberate humans from it. This liberation, of course, does not imply a suicide, or wishing one had never been born; on the contrary, it is an active quest for the source of Light. It requires determination. It is a search for not merely existence, but Life; not only living, but being "all in act." A precondition of this quest is the "indifference of the spirit" or the uprooting of the heart from the many attachments of the ego and the confinements of the sensorial world, from the fetters of existence, and the vicissitudes of life. Once this Liberation is attained, we can say with Christ that we are "in the world but not of it." This Liberation is an attitude of detachment: an inner serenity in the face of the many adversaries of life. Further, from a certain point we can say that the entire work of Rumi: all those mystical ghazals and metaphysical teachings of his Mathnawi, is an invitation to this Liberation; on the condition that we take the medicine that he prescribes no matter how bitter it may be.

Rumi's comparison of the world to a prison is derived from a famous Hadith by the Prophet, which reads:

The world is the paradise of the infidel and the prison of the believer (Tradition of the Prophet)

This world is a prison, and we are the prisoners

dig a hole in this prison,

seek escape. (I, 982)

Since the world is sick and a prisoner,

What wonder if the sick one is becoming extinct? (I, 1295)

This world is an exceeding dark and narrow pit,

Outside is a world without scent or color. (III, 64)

As to the commentary on the above verse, Foruzanfar, the eminent Rumi scholar has written,

The world is sick because it is subject to calamities and like the sick person, it loses its vitality. And whatever is liable to calamity, its dissolution is conceivable. The fact that the world is a prison can be explained in two ways: firstly, because it is condemned to divine verdict and natural laws. Hence it is not immune to transformation and the occurrence of calamities, and generation and corruption.4

Again, he says,

The fact that the world is a prison can be justified in two ways: first, because the world is subject to divine decree and natural laws, and thus it is not impervious to the appearance of misery, atrophy, change and generation and destruction...5

In order to explain the narrowness of the world and the existence of other realms, Rumi often makes use of a recurring analogy and compares the material world to the mother's womb and humans to the embryo. To the embryo, the existence of another world is inconceivable. It is hard for the embryo to imagine anything other than the mother’s womb or blood. No matter how many times we describe the colors, scents, and the beauties of nature, and all the pleasures the world can offer, the embryo would fail to understand it. Similarly, when prophets and saints describe to us the nature of the other world, it makes no sense, because, as Rumi says, our "blind imagination" can form no conception of it. We feel safe in our own confinement, and deem anything other than this to be unreal and "superstition." As Rumi put it,

If anyone were to say to the embryo in the womb,

"Outside is a world supremely ordered, a pleasant earth,

Broad and long. In it there are hundred delights and many

Things to eat.

Mountains and seas and plains, fragrant orchards,

Gardens and sown fields.

A sky very lofty and full of light,

Sun and moonbeams and a hundred stars.

The marvels come not into description,

Why are you in tribulation in this darkness?

Why do you drink blood on the gibbet of this

Narrow place in the midst of confinement and

Filth and pain?"

The embryo, in virtue of its present state, would be disbelieving,

and would turn away from this message.

Saying, “This is absurd and a deceit, a delusion,”

Because the blind imagination has no image (of it).

Insofar as the embryo’s perception has not seen

Anything of the kind, its disbelieving perception

would not listen (to the truth).

Just as in this world the Saints speak of that other world

To the common folk, saying,

This world is an exceeding dark and narrow pit,

Outside is a world without scent or color.

None of their words entered into the ear of a single one of them,

For this sensual desire is a barrier huge and heavy.

Desire prevents the ear from hearing,

Self-interest closes the eye from beholding.

Even as, in the case of the embryo, desire for the blood which is

Its nourishment in the low abodes

Debarred it from the news of this world,

It knows no breakfast but blood.

(III, 53- 68)

Our aim in this article was to provide a brief introduction to Rumi’s cosmological worldview. We have mentioned that Rumi's central concern was not cosmology, but anthropology and theology; that in his limited references to the gradation of being, he views the world in a ternary fashion: composed of Nonbeing, which is the fountainhead of life and the ultimate Source from which everything comes forth; the Imaginal, which is issued from nonbeing, and which is situated "below" nonbeing and "above" the sensory world, and which can be perceived by the organ proportioned to it, namely the cognitive Imagination; and finally the sensorial world, which occupies the lowest level of this tripartite cosmology, and is a place of strife, opposites, and multiplicity.

- S.H. Nasr, Science and Civilization in Islam, p. 92-93.

- Joint perception. An innate organ which gathers sense-data acquired through the five senses. Avicenna corresponds this with the Greek term, Phantasia.

- “The Hindu notion of "Illusion," Maya, coincides in fact with the Islamic symbolism of the "Veil," Hijab: The universal Illusion is a power which on the one hand hides and on the other hand reveals; it is the Veil before the Face of Allah or, according to a multiplying extension of the symbolism, the series of sixty-six thousand veils of light and darkness which either through clemency or rigor screen the fulgurating radiance of the Divinity.” Frithjof Schuon, The Mystery of the Veil.

- Sharh-i Mathnawi-e Sharif (Commentary on the Noble Mathnawi).

- Ibid.