An Intro to Saint Gregory of Nyssa and His Last Work: The Life of Moses

My five year old daughter speaks with reverence about a “family tradition” involving the two of us walking down the Greenbelt trail near our home to The Tiger Eye coffeeshop where she loves to get a small cotton candy ice cream. It’s hardly a family tradition as we’ve been in this home only two or three years. And for my part, I quietly long for the day when she matures beyond that ice cream flavor choice for herself. However, it is a simple local outing that I enjoy with her and that we have done as a whole family a few times. Recently, when my three kids and I were all indulging in this “family tradition,” we noticed several shelves of books labeled “Free Library” up above us on the covered porch where we were sitting. My youngest asked me to find a book for her, so I searched for a while and found a book of poems that she got excited about. We were throwing away ice cream cups and napkins as we got ready to go, when my oldest daughter, who just graduated from high school, reached up to pull a book off the shelves that I had not noticed. She said, “Dad, isn’t this a saint that you love to talk about?”

Sure enough, it was a copy of The Life of Moses by Gregory of Nyssa—the HarperCollins Spiritual Classics edition printed in 2006 with a forward by Kentucky novelist Silas House. HarperCollins used the 1978 English translation by two Harvard scholars, Abraham Malherbe and Everett Ferguson that was first published by Paulist Press with a brief preface by John Meyendorff. This remains the only complete translation in English (with only portions of the text having been translated and published in 1961 by Herbert Musurillo in From Glory to Glory: Texts from Gregory of Nyssa’s Mystical Writings).

We brought the book home, and I recently finished reading it. I had read it once before a few years back in a digital form. This second time, I enjoyed holding a real book in hand. My first time through, to be honest, had been a hasty skim-read, with minimal comprehension on my part. For this second reading, because of other reading that I’ve done in the meantime, I was also better prepared to follow Gregory’s thinking.

Malherbe and Ferguson conclude that Gregory wrote this text in the early 390s, during the last five years of his life as he neared his death at about sixty. Born in 335, ten years after the First Council of Nicaea and then attending the First Council of Constantinople in 381, Gregory lived during a period of intense and widespread doctrinal controversies in the church, and his family was instrumental in securing the success of Nicaea’s creedal formula. The youngest member of a prominent and propertied family in Cappadocia with three generations of saints, this lineage had been tutored in its first generation as Christians by Gregory the Wonderworker who had been a devoted and distinguished student of Origen in Alexandria.

In the third generation, to which Gregory belonged, his oldest sister, Macrina, took up most of the responsibility for the household. Their paternal grandmother, Macrina the Elder, died in the early 340s, and their father, Basil the Elder, a lawyer and rhetorician, died around 345, leaving behind nine children who had survived childhood (and of whom five, or possibly six, are remembered by name). This left thirty years during which the oldest child, Macrina, cared for her aging mother, Emilia, until her mother’s death in 375. In the midst of these years, one of Macrina’s four brothers, Naucratius, died during a hunting accident in 357. Naucratius had been a lawyer like his father and had also learned to hunt in support of his family when they had occasionally needed to flee into the hills amid the violent doctrinal controversies that swept through the region. This premature death of a sibling gathered home the grown and grieving children for a time and ultimately shifted even more responsibility onto Macrina’s shoulders.

Macrina’s four sisters all married. Macrina herself was betrothed, but her promised husband died before their wedding. After this and the death of her father, wanting to start a community of female monastics on their family estate, Macrina persuaded her mother to join her and received support from Basil, now the oldest male in the household. With the start of this community, Macrina freed the household slaves and some of these chose to join the Christian community. Macrina’s three surviving brothers—Basil, Gregory and Peter—were devoted to her and were clearly influenced by her example of Christian service. All three eventually devoted their own lives to serve the church. When Basil and his friend Gregory of Nazianzus returned from the most prominent overseas schools of that day with ideas of taking up public careers, Macrina encouraged them to undertake a year of retreat and to spend it studying Origen’s works. They recorded the passages that they found most instructive in what is now the Philocalia of Origen (one of the few collections of his works to survive the many fires of future centuries). This labor by Basil no doubt connected back to the family’s generational love of Origen and of his greatest student, Gregory the Wonderworker, who Basil’s grandmother Macrina the Elder used to quote at length from memory.

Although Basil and his friend attended distinguished schools overseas, his younger brother Gregory did not have that opportunity. He was educated primarily by his older siblings, Macrina and Basil. While pursuing a career in rhetoric as a young man, Gregory was married and then later widowed. This experience of marriage is one aspect that makes Gregory of Nyssa’s writings unique among the fathers and mothers in the church, almost all of whom pursued monastic life from their youth.

Gregory was appointed as the bishop of Nyssa in 372 and wrote his Great Catechism (or Catechetical Discourse) during this time as a help in teaching his flock. It describes salvation as a case of the devil being tricked into welcoming God himself (unrecognizable to the devil as a crucified human body) down into hell so that life itself “was introduced into the house of death” and “he who first deceived man …not only conferred benefit on the lost one [humanity], but on him, too, who had wrought our ruin” (chapters 24 to 26). Two other times in this same work, Gregory refers to the devil’s salvation: “Even the adversary himself will not be likely to dispute that what took place was both just and salutary” and finally stating that Christ “accomplished all the results before mentioned, freeing both man from evil, and healing even the introducer of evil himself” (chapter 26). Clearly, in Gregory’s day, there was no reason for a bishop not to teach his flock that Christ’s descent into hell would ultimately save even the fallen angelic powers.

During 379, a year when Gregory lost both Basil and Macrina, Gregory preached a sermon denouncing slavery and challenging members of his wealthy congregation to free their slaves. This sermon, based on a text from Ecclesiastes, came during the season of lenten preparation for Easter shortly after his brother’s death in January and not long before he would lose his sister in July. Of this sermon, David Bentley Hart writes: “Nowhere in the literary remains of antiquity is there another document quite comparable to Gregory of Nyssa’s fourth homily on the book of Ecclesiastes: certainly no other ancient text still known to us—Christian, Jewish, or Pagan—contains so fierce, unequivocal, and indignant a condemnation of the institution of slavery.” (From “The ‘Whole Humanity’: Gregory of Nyssa’s Critique of Slavery in Light of His Eschatology” in the Scottish Journal of Theology, 54.1, February 2001, pp. 51-69.)

This reverence for the interconnectedness of all humans was not the only way in which Gregory was inspired by his sister. His work On the Soul and the Resurrection was written shortly after he lost Macrina and in the form of a dialog with Macrina on her deathbed. Their conversation is a response to Plato’s Phaedo as Macrina answers many doubts and fears that Gregory relates. At one point, Macrina gives this answer to her brother:

Evil must be altogether removed in every way from being, and, as we have said before, that which does not really exist must cease to exist at all. Since evil does not exist by its nature outside of free choice, when all choice is in God, evil will suffer a complete annihilation because no receptacle remains for it.

This concentrated theological and metaphysical insight, recorded as the words of Macrina, claims that existence and evil are entirely incompatible, and that evil can only exist as long as any choices remain that are in opposition to existence itself. However, once all choices have been made in favor of existence (which is God’s gift of divine life to creation), then there can be no basis for evil to have any form of existence. Macrina’s language is so demanding and complete here, that she is evidently including every creaturely choice across all of time as we know it when she speaks of that day when we can say that “all choice is in God.” Eventually, every creature will decide to complete every decision or action that they ever started so that their every choice will eventually be “in God.” At that point, no evil will remain, not even as a memory of our once incomplete and broken choices (see here). Every choice in opposition to God’s offer of life will have been replaced by a choice to accept God’s offer of divine and infinite life. (I will return to this astounding vision below while considering a passage from The Life of Moses.) Staying with On the Soul and the Resurrection for a moment more, Gregory has Macrina describe the end of all things in this way:

When God brings our nature back to the first state of man by the resurrection, it would be pointless to mention such matters [i.e., all the contextual details that influence our behavior in this lifetime] and to suppose that the power of God is hindered from this goal by such obstructions. He has one goal: when the whole fullness of our nature has been perfected in each man, …God intends to set before everyone the participation of the good things in Him, which the Scripture says eye has not seen nor ear heard, nor thought attained. This is nothing else, according to my judgment, but to be in God Himself. …No longer will rational beings be divided by different degrees of participation in equal good things. Those who are now outside because of evil will eventually come inside the sanctuary of divine blessedness, …for all of whom one harmonious festival will prevail.

Gregory of Nyssa also interacted with others of his siblings through his theological writings. After the death of Basil, he wrote an account of the creation of humankind that expanded upon Basil’s Hexaemeron and responded to Plato’s Timaeus. He dedicated this work to his only living brother, Peter, Bishop of Sebaste with a heartfelt letter. Gregory’s insights in this work also continue to astound scholars to this day with a new English translation and full critical edition of the Greek text (both by Fr. John Behr) due to be published near the end of 2022 or start of 2023 by Oxford University Press. For example, Gregory says that the image of God is only fully displayed when every human person is included, so that the reference in Genesis to making humanity in God’s image is actually a reference to all of humanity as one body (which is ultimately the body of Jesus Christ that is also revealed at the end of time):

In the Divine foreknowledge and power all humanity is included in the first creation. …The entire plenitude of humanity was included by the God of all, by His power of foreknowledge, as it were in one body, and …this is what the text teaches us which says, God created man, in the image of God created He him. For the image …extends equally to all the race. …The Image of God, which we behold in universal humanity, had its consummation then. …He saw, Who knows all things even before they be, comprehending them in His knowledge, how great in number humanity will be in the sum of its individuals. …For when …the full complement of human nature has reached the limit of the pre-determined measure, because there is no longer anything to be made up in the way of increase to the number of souls, [Paul] teaches us that the change in existing things will take place in an instant of time. [And Paul gives to] that limit of time which has no parts or extension the names of a moment and the twinkling of an eye (1 Corinthians 15:51-52).

Two years after the death of Basil and Macrina, Gregory attended the First Council of Constantinople, in the year 381. He was then asked to serve on a series of difficult and largely unsuccessful assignments to restore peace and doctrinal unity in multiple places far from home. During these years, Gregory of Nazianzus (the dear friend of Basil and the entire family) died in 390 and Gregory’s brother Peter also died the next year, in 391. Therefore, when Gregory wrote The Life of Moses, he was not only old but largely alone in the world—almost the last living member of a large and close-knit family. Moreover, his own most recent past contained what was essentially a series of difficult diplomatic and administrative failures.

At this stage of his life, Gregory received a letter from Caesarius (identified as a young monk in some manuscripts but otherwise unknown) that asks the elderly Gregory for advice on how to achieve a perfect life. In his response, Gregory turned to Moses as an inspiration, and Gregory’s account of Moses moves from glory to glory. Gregory calls us to follow Moses as he pursues God ever more—striving always to receive our life anew and in full from the infinite life of God:

[Moses] shone with glory. And although lifted up through such lofty experiences, he is still unsatisfied in his desire for more. He still thirsts for that with which he constantly filled himself to capacity, and he asks to attain as if he had never partaken, beseeching God to appear to him, not according to his capacity to partake, but according to God’s true being. Such an experience seems to me to belong to the soul which loves what is beautiful.

Gregory understands beauty to result from the infinite overflow of God’s life and glory (see Beauty of the Infinite by David Bentley Hart as well as Beauty: a Theological Engagement with Gregory of Nyssa by Natalie Carnes), and we are to orient everything in response to this endless overflow of the Spirit’s glorious life and light. Greogry connects virtue itself to the ceaseless pursuit of God rather than seeing virtue as a skill or habit to be mastered. Virtue, Gregory insists, is impossible to perfectly master because its goal is infinite and its one enemy is any pause to rest content in what has come before: “Just as the end of life is the beginning of death, so also stopping in the race of virtue marks the beginning of the race of evil.” We rest only in the current presence of an infinitely good God who calls us always to receive more.

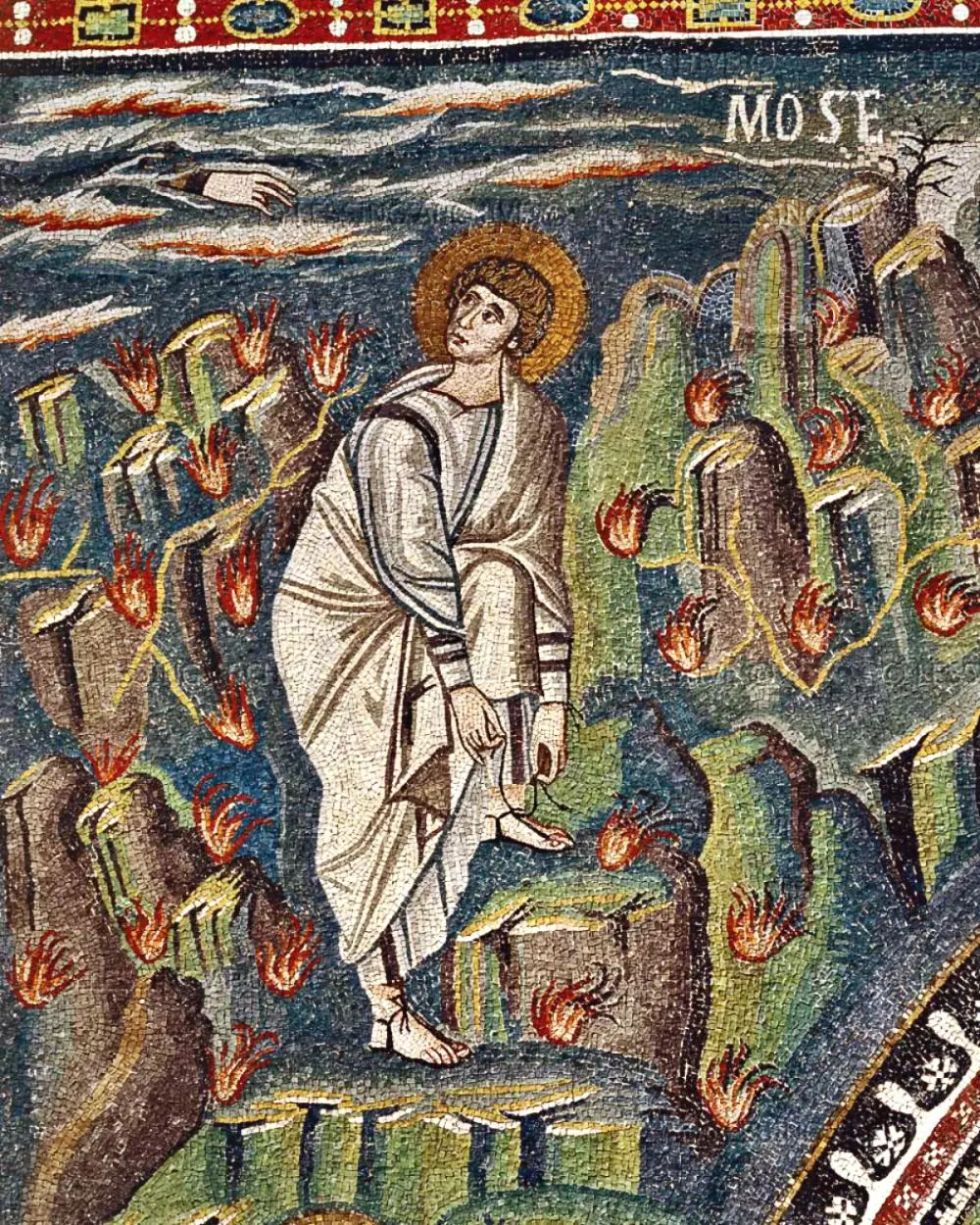

When listing the many achievements by Moses, Gregory always moves from what he calls the “literal” account to the “spiritual” or “real” sense of the story. This spiritual meaning always involves the life of our own heart or mind in relation to God in so far as it is illuminated by the light of Christ. For example, to very briefly describe what Moses did after he fled Egypt to live in the wilderness with those who tended sheep, Gregory says: “In himself, Moses shepherded a flock of tame animals.” (Incidentally, Christ uses many images of sheep to teach us about our own hearts, and this image of a heart full of herd animals can provide a wonderful understanding of Christ’s account of the separation of the sheep from the goats which he provides as a way of understanding God’s judgment. However, that would be too much of an aside to develop.)

This focus on the life of our heart (or our perceptive mind, nous, with its source in God) is grounded in the literal account of Moses. Gregory points out that by “taking a hint from …Paul, who partially uncovered the mystery of these things,” we understand that the tabernacle not made by hands (2 Corinthians 5:1) which was the pattern or archetype according to which God told Moses to build an earthly model (Exodus 26:30) was Christ himself, the eternal “tabernacle which encompasses the universe.” In this passage, Gregory connects together the contemplation of Christ with the contemplation of all creation (the cosmos) and claims that this is the vision that Moses received on Mount Sinai. With this light of Christ revealed to Moses, Gregory shares a common ground with Moses so that every literal event in the life of Moses is also a shared spiritual event with Gregory himself, as both men share the same pursuit of Christ. With all of this, the possibilities for further reflection, synthesis and exposition are endless, and Gregory clearly wishes for his readers to pick up and reflect further just as Gregory himself picks up from Paul who only “partially uncovered the mystery of these things.”

This spiritual reading was not just something that the church fathers did to “deal with” uncomfortable passages in the Old Testament (although Gregory does point out that such passages can confuse readers without this spiritual method of reading). Instead, this spiritual reading was simply the most significant way to read all texts. It is how ancient people understood language to work. Gregory even allegorizes Christ’s own words. Speaking about the story where Moses assures victory in battle by keeping his staff raised above his head, Gregory takes an image from Christ’s teaching to connect it, in reverse, back to this image of Moses with outstretched arms:

Moses’s holding his hands aloft signifies the contemplation of the Law with lofty insights; his letting them hang to earth signifies the mean and lowly literal exposition and observance of the Law. …For truly, to those who are able to see, the mystery of the cross is especially contemplated in the Law. Wherefore the Gospel says somewhere that ‘not one dot, not one little stroke, shall disappear from the Law’ [Matt. 5:18], signifying in these words the vertical and horizontal lines by which the form of the cross is drawn. That which was seen in Moses, who is perceived in the Law’s place, is appointed as the cause and monument of victory to those who look at it.

This kind of reading was universal in the ancient world. Christians learned it from Jewish and pagan examples, and the great teachers expected their students to hear and to understand images and words in such ways. For Gregory, however, a truly spiritual reading was not simply a method of reading but was specifically Christocentric. It was allegorical and symbolic reading that was both inspired by and pointing back to Jesus Christ as the beginning and the end. Therefore, when Gregory equates “the mean and lowly literal exposition and observance of the Law” with the Jewish understanding of the scriptures, he is specifically rejecting their failure to be Christocentric. Jews had always read their own scriptures allegorically but with other guiding lights at the center of their own spiritual readings. Such criticisms of Jewish readings among church fathers easily slipped into antisemitism, or seemed to imply that only Christians had practices of spiritual reading. However, the insistence upon an allegorical reading that keeps Christ central would have been understood as one of the most basic functions of being a Christian. Religious and philosophical schools in antiquity were distinguished not only by having distinct sacred texts but also by the central vision that guided their readings.

One simple way to sum up all of this is that Gregory considers virtue to be acquired and maintained by continual devotion to Jesus Christ in contemplation and prayer. In such attentive openness, we learn to desire God’s infinite beauty more and more, expecting to see more of our Creator each day. This pursuit of God is new each moment because of its infinite horizon. But it is always found now, in this moment as the present is always our only contact point with eternity. Gregory commends a daily and steady chasing after all that is most real:

For the truth of reality is truly a holy thing, a holy of holies. …Believe that what is sought does exist, not that it lies visible to all, but that it remains in the secret and ineffable areas of the [seeing mind].

“Seeing mind” is my own alteration of the translation (replacing “intelligence”). Without having the Greek text, I’m assuming that the word here is nous which is a critical term related to prayer and contemplation. If that is the case, then “intelligence” is a poor choice. Nous is often translated as “mind” or “intellect.” However, used by a contemplative such as Gregory, it refers specifically to our innermost organ of vision (the core of our intellect) whereby we can directly see and enjoy the greatest of realities, i.e. look upon and participate in the shared life of God that lies within and animates everything real that surrounds us. Gregory would have associated “nous” with the “single eye” of Matthew 6:22 or Luke 11:34 that fills our whole body with light.

For the Greek philosophical traditions, the nous was “distinguished from discursive thought and applies to the apprehension of eternal intelligible substances and first principles” and was “sometimes identified with the highest or divine intellect” (from “nous: Greek philosophy” in Encyclopedia Britannica, 16 June 2013, accessed 18 July 2022, most recently revised and updated by Brian Duignan). Despite abuses and misrepresentations by a few gnostic sects, this capacity for the highest or divine sight was not understood by almost any ancient philosophers or Christians to be separate from our physical sensations and from the material world of our bodies and the cosmos. Instead, the nous perceives God by means of synthesizing our sensory perceptions into a whole that recognizes the interconnected life and light animating and sustaining everything in our world.

Such a vision of God—as both infinitely beyond us and present in all of reality—cannot be grasped or sustained in any static encounter. Such a God can only be encountered in a continual pursuit. As the later disciple of Dionysius the Areopagite writes, such a God can only be manifested in a revelation that hides the ultimate source of what is revealed. Any complete revelation of the infinite God cannot be a true revelation of that God. Gregory expresses this with a reflection on why Moses saw only God’s back while hidden within the crevice of the rock:

So Moses, who eagerly seeks to behold God, is now taught how he can behold him: to follow God wherever he might lead is to behold God. …He who leads, then, by his guidance shows the way to the one following. He who follows will not turn aside from the right way if he always keeps the back of his leader in view. For he who moves to one side or brings himself to face his guide assumes another direction for himself than the one his guide shows him …for good does not look good in the face, but follows it. …What looks virtue in the face is evil. But virtue is not perceived in contrast to virtue. Therefore, Moses does not look God in the face, but looks at his back; for whoever looks at him face-to-face shall not live.

This is where Gregory perhaps most fully expresses his point that virtue is only possible with both ongoing action and growth in pursuit of more beauty and goodness. To think that we have ever possessed God is to have lost God. This is not to say that anyone could stay so deluded forever. In his last work, Gregory continues to assume the universal restoration that he taught in all his works across his lifetime. As with his other works, this topic only comes up in passing and is never directly addressed or defended as if it could be taken for granted.

For example, when writing about the ten plagues, Gregory observes that, “after three days of distress in darkness the Egyptians did share in the light.” He says that this restoration of light to the Egyptians is like “the final restoration which is expected to take place later in the kingdom of heaven” for “those who have suffered condemnation in Gehenna.” He concludes:

For that ‘darkness that could be felt’ [Exod. 10:21], as the history says, has a great affinity both in its name and in its actual meaning to the ‘exterior darkness’ [Matt. 8:12]. Both are dispelled when Moses, as we have perceived before, stretched forth his hands on behalf of those in darkness.

Gregory’s concept of this “final restoration” ultimately echoes the passage above from On the Soul and the Resurrection where Gregory has Macrina speak of a completion or fulfillment of time “when all choice is in God.” In a reflection on the account of Moses having the golden calf pulverized, mixed with water, and drank by the people, Gregory envisions a time where every evil is replaced by goodness as every idol worshiper takes up true religion and swallows their own past idols:

The error of idolatry utterly disappeared from life, being swallowed by pious mouths, which through good confession bring about the destruction of the material of godlessness. The mysteries established of old by idolaters became running water, completely liquid, a water swallowed by the very mouths of those who were at one time idol-mad. When you see those who formerly stooped under such vanity now destroying those things in which they had trusted, does the history then not seem to you to cry out clearly that every idol will then be swallowed by the mouths of those who have left error for true religion?

This language about how those who did any evil will themselves “bring about the destruction of the material of godlessness” is much like the passage above in Macrina’s words where “evil will suffer a complete annihilation because no receptacle remains for it.” And this is also the same idea picked up by George MacDonald:

Annihilation itself is no death to evil. Only good where evil was, is evil dead. An evil thing must live with its evil until it chooses to be good. That alone is the slaying of evil. (Lilith)

In our endless pursuit together of life with our infinite God, there comes a point where “all choice is in God” and evil no longer even has any place where it might have once existed (see here). Evil and suffering are, then, no longer past or future possibilities, and yet our pursuit of God remains unchanged and endless. Remarkably, this boundary line of evil’s utter destruction (and of having achieved theosis) is virtually invisible within The Life of Moses because its achievement starts now and its fruit continues in an eternity of growth and pursuit. So I wait for my five year old daughter to mature beyond cotton candy ice cream to even more wonderful flavors. Yet our enjoyment of our next walk down Parkway Creek to The Tiger Eye (where I will return The Life of Moses to the free library on the side porch) will already participate in all the goodness that my daughter and I have to enjoy together in not only a lifetime but in an eternity with the God of creeks and ice cream and free libraries.

Moses Guarding the Flock and at the Burning Bush (6th cent. mosaic, Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna, Italy)