An Introduction to Sophia and Sophiology

Sophiology is most strongly associated with Sergei Bulgakov (l87l–l944) who faced official condemnation for his writings on the subject in 1935 by Patriarch Sergey of Moscow and the Synod of Karlovci (Yugoslavia). Following this, Bulgakov’s own bishop, Metropolitan Eulogius of Paris, established a committee to examine his work. They found his system questionable but not heretical, and they issued no formal censure (although a minority report written by two members of the committee, including Georges Florovsky, did recommend formal censure of Bulgakov). Despite the controversies, Metropolitan Eulogius of Paris and most of Bulgakov’s colleagues at the institute supported him and protected his freedom to teach and to write.

The eminent Anglican scholar E. L. Mascall gave this summary in his 1943 book He Who Is: A Study in Traditional Theism (p. 112):

It should be pointed out that Mensbrugghe is by np. means the only modern Russian theologian who has discussed the problem of creation in the light of the conception of the Divine Sophia. There is a line of development going back through Fr. Paul Florensky to Vladimir Solovyev. And a Sophiology in many respects different from that of Mensbrugghe has been worked out by the distinguished Dean of the Russian Theological Academy in Paris, the Archpriest Sergius Bulgakov; his only work on the subject in English, apart from a few articles in Theology (July and August 1931, January 1934), is The Wisdom of God. For him, the divine ousia and sophia are identical; sophia is the self-revelation of the Godhead and belongs to all three Persons of the Trinity. Sophianity (which is identical with theandrism, the ultimate unity of Godhead and manhood which is manifested in the fact that man is made in the image of God) is a general metaphysical and theological principle, which provides a particular understanding not only of the doctrine of God, but also of cosmology, anthropology, Christology, pneumatology, Mariology and ecclesiology. Bulgakov insists very strongly upon the distinction between God and the world, and upon the fact that the world is not necessary to God; “ The world as such maintains its existence and its identity, distinct from that of God. . . . There is no such ontological necessity for the world as could constrain God himself to create it for the sake of his own development or fulfilment; such an idea would indeed be pure pantheism’* (op. cit., p. no). Distinction is made between the uncreated sophia^ which is the locus of the divine prototypes of all possible creatures, and the creaturely sophia found in the actual world. “Here we have at once Sophia in both its aspects, divine and creaturely. Sophia unites God with the world as the one common principle, the divine ground of creaturely existence. Remaining one, it exists in two modes, eternal and temporal, divine and creaturely.”

With significant precedents in the theology of Jakob Böhme (1575-1624), a Lutheran Protestant philosopher and mystic, Sophiology was first developed by Vladimir Solovyov (1853–1900) and by the poet Alexander Blok (1880–1921). It was also developed in the theological writings of Pavel Florensky (1882–1937) as well as the writings and iconography Mother Maria Skobtsova (1891–1945) who was recognized as a saint by the Ecumenical Patriarchate in 2004. Kateřina Bauerová writes: “Mother Maria continued, theologically, in the Sophiological legacy of the religious philosopher Vladimir Solovyov (1853–1900), the poet Alexander Blok (1880–1921), and her spiritual father, the theologian Sergei Bulgakov (l87l–l944).” [From “Motherhood as a Space for the Other” in Feminist Theology. Vol. 26.2 (2018) 133 –146.]

Below is a watercolor icon of Sophia by Mother Maria Skobtsova called “In the Garden of Eden” from 1937. As Kateřina Bauerová shares:

The image is based on the biblical motif from the Revelation of John (12:13–14) about the battle of good and evil: “And when the dragon saw that he was cast to the earth, he persecuted the woman who brought forth the man-child. And the Woman was given the two wings of the great eagle that she might fly into the wilderness into her place, where she nourished for a time and times and half a time from the face of the servant.” It is reminiscent of a synthesis of Novgorodian and Kievian iconographic types of Holy Wisdom. [For more on this, see Kateřina Bauerová. “The Masculine and the Feminine Dimensions of Being Human in the Icons of Sister Julia Reitlinger and Mother Maria Skobtsova.” Logos: A Journal of Eastern Christian Studies. Vol. 56.1–2 (2015) 323–40.]

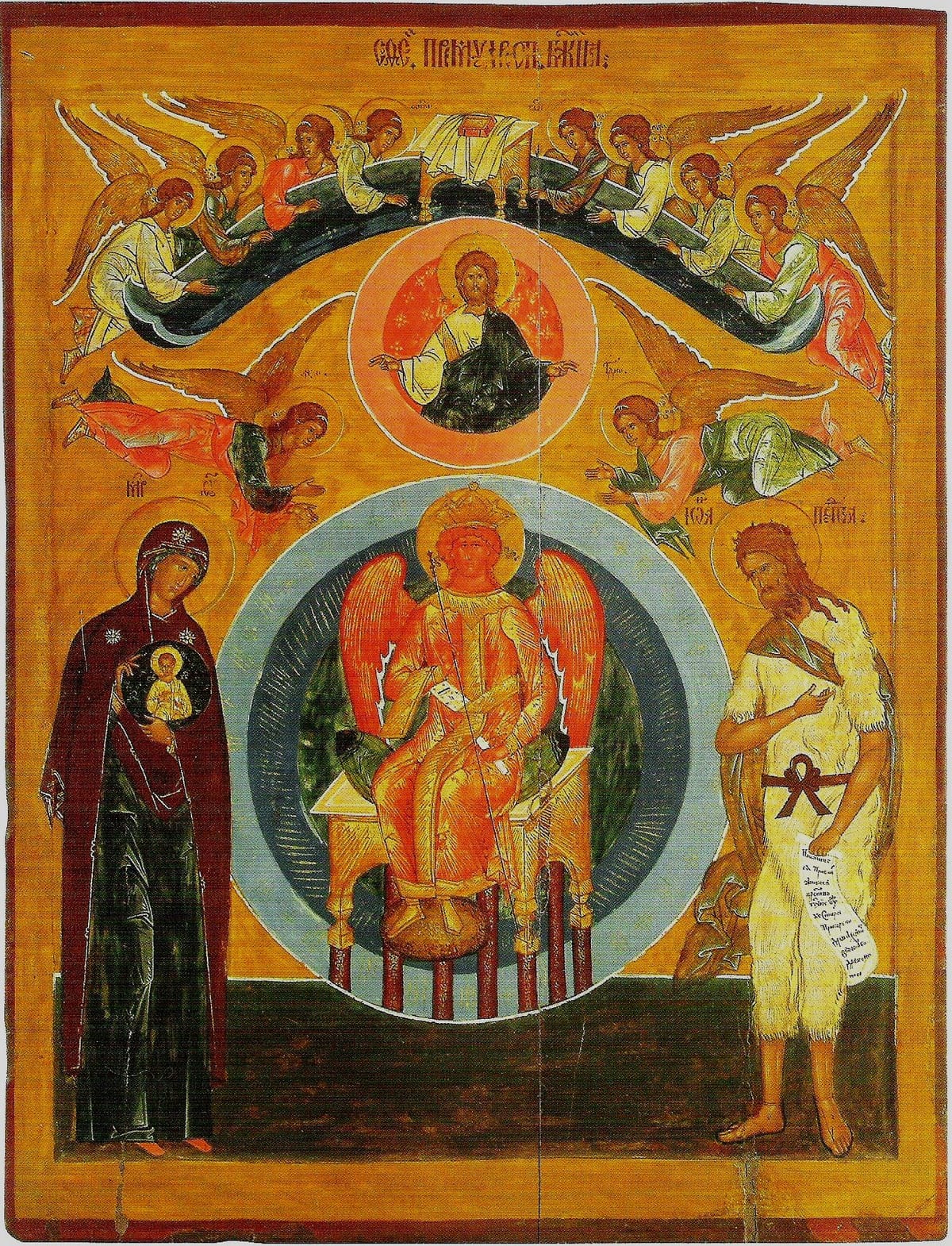

Sophia’s presence in the Russian iconographic tradition is first as a “enthroned angel” known as the “Novgorod” type because it first appeared in the northern trading city of Novgorod in the 15th century.

The later “Kiev” icon type is noted for its groups of sevens. It is customarily painted in a Westerized manner that was adopted in some Russian icon painting in the latter half of the 17th century.

In addition to Orthodox thought, Sophiology has found substantial recognition among Catholic theologians and leaders. Thomas Merton studied the Russian Sophiologists and praised Sophia in his poem titled “Hagia Sophia” (1963). Valentin Tomberg incorporated many Sophiological insights in Meditations on the Tarot. The book’s 2020 Angelico Press edition includes an introduction written by Robert Spaemann, a favorite theologian of Pope Benedict XVI, while its other editions feature an afterword by Hans Urs von Balthasar. Pope John Paul II elevated von Balthasar to cardinal after von Balthasar had endorsed this book, and the pope himself was photographed with Tomberg’s book on his desk and was said by Richard Payne (the original English publisher) to have kept a copy on his nightstand. Contemporary author Michael Martin has continued to publish on the topic, primarily with Angelico Press. Finally, Anglican theologian Rowan Williams has included substantial references to Sophiology in his 2021 book Looking East in Winter: Contemporary Thought and the Eastern Christian Tradition.

As for a theological introduction, here is a helpful overview from David Bentley Hart’s forward to Solovyov’s Justification of the Good:

The figure of Sophia, admittedly, arouses more than a little suspicion among even Solovyov’s more indulgent Christian readers, and some would prefer to write her off as a figment of the young Solovyov’s dreamier moods, or as a sentimental souvenir of his youthful dalliance with the Gnostics. To his less indulgent readers, she is something rather more sinister. And indeed it is difficult to know what exactly to make of the two visions of Sophia that Solovyov had in 1875–the first in the British Museum, the second in the Egyptian desert–or the earlier vision he had at the age of nine. But it is important to note that, in Solovyov’s developed reflections upon this figure (and in those of his successor Sophiologists,’ Pavel Florensky and Sergei Bulgakov), she was most definitely not an occult, or pagan, or Gnostic goddess, nor was she a fugitive from some Chaldean mystery cult, nor was she a speculative perversion of the Christian doctrine of God. She was not a fourth hypostasis in the Godhead, nor a fallen fragment of God, nor a literal world-soul, nor an eternal hypostasis who became incarnate as the Mother of God, nor most certainly the ‘feminine aspect of deity.’ Solovyov possessed too refined a mind to fall prey to the lure of cultic mythologies or childish anthropomorphisms, despite his interest in Gnosticism (or at least in its special pathos); and all such characterizations of the figure of Sophia are the result of misreadings (though, one must grant, misreadings partly occasioned by the young Solovyov’s penchant for poetic hyperbole).

In truth, the divine Sophia is first and foremost a biblical figure, and ‘Sophiology’ was born of an honest attempt to interpret intelligibly the role ascribed to her in the Wisdom literature of the Old Testament, in such a way as to complement the Logos Christology of the Fourth Gospel, while still not neglecting the ‘autonomy’ of creation within its very dependency upon the Logos. Solovyov’s Sophia stands in the interval between God and world, as an emblem of the nuptial mystery of Christ’s love for creation and creation’s longing for the Logos. Sophia is the divine Wisdom as residing in the non-divine; she is the mirror of the Logos and the light of the Spirit, reflecting in the created order the rational coherence and transcendent beauty in which all things live, move, and have their being. She is also, therefore, the deep and pervasive Wisdom of the world who, even as that world languishes in bondage to sin, longs to be joined to her maker in an eternal embrace, and arrays herself in every palpable glory and ornament to prepare for his coming, and by her loveliness manifests her insatiable yearning.

Another way of saying this is that Sophia is creation–and especially human creation–as God eternally intends, sees, loves, and possesses it. The world is created in the Logos and belongs to him, shines with the imperishable beauty of the Father made visible in him, and in the Logos nothing can be found wanting; thus one may say that he, in his transcendence, eternally possesses a world, and that the world, in its immanence, restlessly longs for him. And yet another way of saying this is that Sophia is humankind (which contains within itself all the lower orders of creation) as God eternally chooses it to be his body, the place of his indwelling, and in his eternity this humanity is perfect and sinless, while in our world it is something toward which all finite reality strives, as its eschatological horizon. One can thus speak of an eternal Christ: the Logos as forever turned toward a world, a world gathered to himself from before all the ages just as–in time–we see the world gathered to him in his incarnation. Here Solovyov is following a line of thought with quite respectable patristic pedigrees: seen thus, as the body of the Logos (the totus Christus in its eternal or eschatological aspect), Sophia is scarcely distinguishable from the eternal Anthropos of whom Gregory of Nyssa writes in On the Making of Humanity. She is not another hypostasis as such, but is the personal and responsive aspect of the concrete unity of a redeemed creation united to–and so “enhypostatized” by–Christ; or, looked at from below (so to speak), the ‘symphonic’ totality of created hypostases perfectly joined to Christ. She is thus indeed a kind of intelligence in the created order (analogous to the intelligence of the spiritual world of which Augustine speaks in The Confessions), and she is beauty, and order, and eros, but only insofar as she personifies the answer of creation to God’s call, the beloved’s response to the lover’s address; far from a kind of Romantic pantheism, what she represents is creation’s desire for God, its insufficiency in itself, its eternal vocation to be the vessel of his glory and the tabernacle of his indwelling presence. She is, in other words, a figure for the active longing of creation and for its accomplished rest; she is both passion and repose, ardent expectation and final peace. She is still God’s Wisdom, but as mirrored in the intricacy, life, unity, and splendor of created being, and in the unity and love the Church.