Doubting Disciples and "Proof of Death"

Thomas' stipulations are as much proof that Jesus had, in fact, died as they were proof of his resurrection.

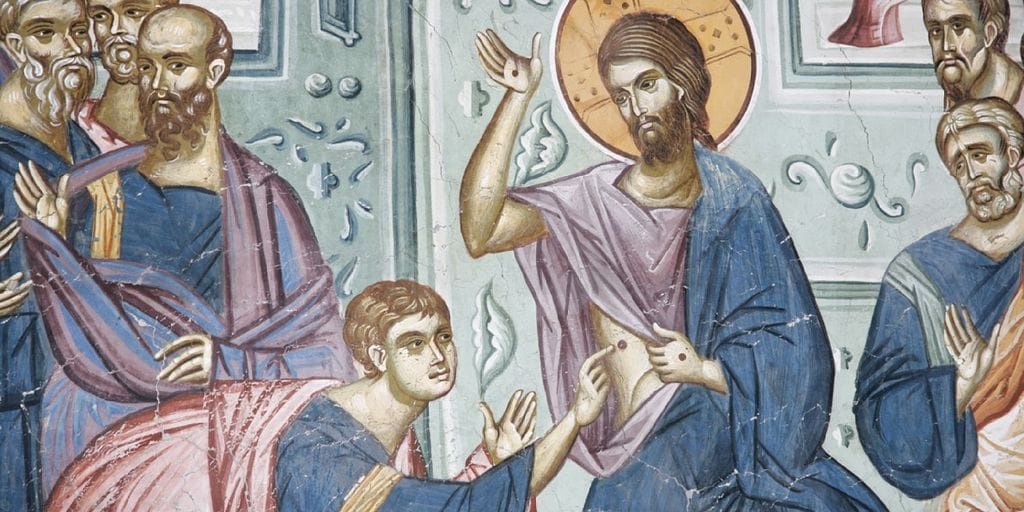

In John's Gospel, Jesus appears on the morning of his resurrection first to Mary Magdalene at the tomb and then, later that evening, to his cowering disciples hiding behind locked doors. He "came and stood among" them and "breathed on them."

According to the text, the Apostle Thomas was not present. No explanation is given, but it wasn't long before he heard the news. "We have seen the Lord," the disciples told him, soon after their experience. Thomas replied, famously:

"Unless I see in his hands the print of the nails, and place my finger in the mark of the nails, and place my hand in his side, I will not believe."

It's this remark – these stipulations – that would forever tarnish Thomas' name. Doubting Thomas he was, and is, because he insisted on seeing before believing. "Have you believed because you have seen me?" Jesus says to him eight days later. "Blessed are those who have not seen and yet believe."

But is the now-infamous moniker really deserved? Indeed, Thomas wasn't the only disciple who needed to see before believing. The disciples were, after all, hiding "for fear of the Jews" when the resurrected Jesus first appeared to them – not exactly a picture of faith. More explicitly, one unnamed disciple who'd run, after Mary Magdalene's report, to investigate the tomb that morning had himself only believed after seeing.

Then the other disciple, who reached the tomb first, also went in, and he saw and believed; for as yet they did not know the scripture, that he must rise from the dead.

Clearly, Thomas isn't unique in his doubt. None of the disciples, it seems, believed without seeing.

So then what is the purpose of the Thomas story?

Thomas' Stipulations

When the other disciples inform Thomas of their experience with the risen Christ, he immediately demands to both see and touch Jesus' wounds – even to place his hand into Jesus' side.

These stipulations seem excessive, maybe, in context. At least 11 other people (including all of the disciples) had attested to witnessing the resurrected Jesus, who himself explained that this was the fulfillment of prophecy. Why insist on more proof?

Well, insisting on this kind of hard evidence is normal when informed about some unlikely event. We are easily deceived. A second opinion can flip firsthand interpretations upside-down.

But why the wounds? Would this serve as proof of identity? Did Thomas believe that, somehow, the disciples may have been duped by an imposter? One who would not have borne the wounds Jesus suffered during his crucifixion?

Or did Thomas suspect his fellow disciples of dishonesty? Was this some game they thought up in his absence – one that would be exposed if the alleged Jesus bore no evidence of the crucifixion that happened just a few days prior?

But regardless of whether Thomas believed his brothers, there's a curious problem with his plan so long as we interpret it as delivering him some kind of "proof" that Jesus lived. That's because Thomas' plan to suspend his belief until he saw and touched Jesus' wounds isn't some kind of fool-proof verification – the wounds themselves are not necessarily some required proof of Jesus' identity, nor do we have reason to believe the disciples would reject the risen Jesus if he bore no wounds. Had Jesus resurrected without his wounds, the disciples might have, ostensibly, still believed. Could not a resurrected body be free of scars and blemishes? His body was allegedly "glorified" in a more substantial way, was it not? The disciples certainly did not seem to have any preconceived notions about what a resurrected Jesus would look like and what sorts of marks he might or might not be allowed to have.

So in that light, what I suspect Thomas demanded (and perhaps before any other disciple), was proof of death. Putting one's hands into healing wounds is not reasonable, or even possible. If Jesus had not died on the cross, but had only "fainted," placing one's hand in his recently-pierced side would be unthinkable.

For Thomas, I think, touching Jesus' wounds would be sure evidence of his death – a reassurance that what happened a few days prior did, in fact, happen and wasn't somehow "erased" or "undone."

But why did Thomas need to know this? And why only Thomas?

Necessary Wounds

Earlier in John's Gospel, Thomas speaks two times.

In John 11, Jesus hears of the death of Lazarus. Jesus' disciples beseech him to stay away from Judea, where Lazarus body lay and where his friends – Mary and Martha – were grieving. "Rabbi," they said, "the Jews were but now seeking to stone you, and are you going there again?" But Jesus persists and offers, in veiled language, a defense of his going to Bethany. It's Thomas who rallies the disciples to Jesus' side – "Let us also go, that we may die with him."

Then in John 14, Jesus speaks to the disciples about his impending departure – "I go to prepare a place for you ... you know the way where I am going." Thomas speaks first in response to this teaching, exhibiting both a profound conviction in Jesus' plans and purpose, but confusion about how to follow him. "Lord, we do not know where you are going; how can we know the way?" he says.

These statements are brief, but they reveal a deep theology surrounding death – and ultimately redemption – gestating in Thomas' mind. First, he was ready to die with Jesus, indicating (I think) his belief in even Jesus' death as a worthwhile act. This stands in contrast to Peter, for example, who questioned the need for Jesus to die in the synoptics' records, and who, in John's Gospel, even rejected the idea with his sword.

Was Thomas already convinced of Jesus' need to die? Did he anticipate it?

Perhaps he was not with the disciples on the evening of Jesus' resurrection because he expected nothing more. Perhaps Thomas was satisfied with what he'd seen – emboldened, even (after all, he was presumably not, like his brothers, scared enough of the Jews to remain hiding with them behind locked doors). Perhaps to die was an important part of Thomas' Christology, and whatever might happen after death was of secondary importance to him.

So when Thomas hears of Jesus' resurrection, what went through his mind? Did he wonder that, if Jesus is alive, he maybe didn't fully die? And if he didn't die, was this maybe not what Thomas had (rightly) come to expect from the Christ?

Thomas' stipulations are as much proof that Jesus had, in fact, suffered and died as they were proof of his resurrection. And I think Thomas knew that if Jesus was to be resurrected in some manner that is meaningful for we who persist to live in "fallen time" even after Easter morning, he must bear his suffering and his death wounds still – a deeper theology of the "glorified wounds" that would be probed and developed only many decades, and even centuries, later by the Church Fathers.