God as One, Two, Three, and Zero: A Rational Defense of the Metaphysics of Christian Doctrine

While it is incomprehensible to our limited minds, it is rationally possible for God to be at once one and two, one and three, alive and dead in the grave.

Many Christian philosophers accept that in order to believe in the rational intelligibility of being, we must accept the principles of noncontradiction and sufficient reason; otherwise, the predictability and meaning on which intelligibility is predicated become impossible.

At the same time, being Christians, they also affirm three major doctrines that appear to violate these principles: the two natures of Christ, the Trinity, and Christ's death on the cross.

We Christians must therefore demonstrate that these seemingly contradictory doctrines are rationally possible, or else be constantly slapped with labels like "irrational" and "intellectually dishonest." While it seems at first impossible to reconcile, there actually exists a comparable situation in math where the sum of an infinite series of numbers can have multiple values when rearranged. We can use this as an analogy for God's infinite being to demonstrate that, while it is incomprehensible to our limited minds, it is rationally possible for God to be at once one and two, one and three, alive and dead in the grave.

In order to function in our world, we must assume that reality is rationally intelligible. Otherwise we could never perform any action and expect a predictable result, since a prediction requires that we understand what we predict. We could not eat breakfast and reasonably expect not to be poisoned. We could not get out of bed and reasonably expect the floor to remain intact. Because we necessarily act as though being is intelligible, it does no good to deny that it is so.

Norris Clarke further argues that, to uphold the intelligibility of being, we must accept the principles of noncontradiction and sufficient reason. The law of noncontradiction states that the same thing cannot be true and false at the same time and in the same way. Without this law, every being would be indistinguishable from its opposite, and all meaning would disappear. The principle of sufficient reason states that every being has a sufficient reason for its existence, either in itself or in some other being. If this were not true, then anything could easily pop in or out of existence at any moment for no reason whatsoever, and rational predictability would be impossible.

These two principles, then, are the necessary foundations for any rational thought.

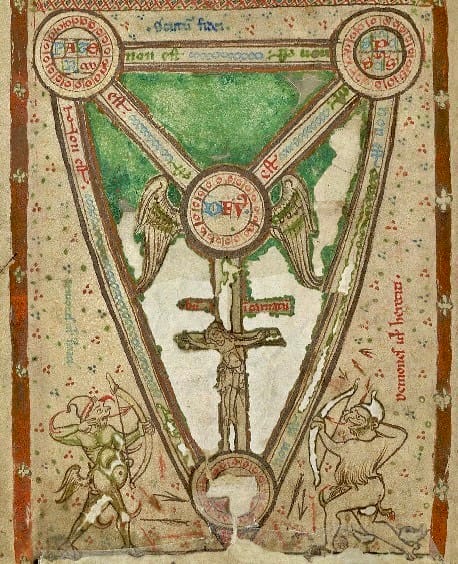

This causes a problem when it comes to certain Christian doctrines. Christianity teaches that there is only one God, and yet He is a Trinity. He is at once three distinct Persons and one simple unity undivided in Himself. It also teaches that Christ is the second person of the Holy Trinity, and is therefore completely God, but that He also took on human nature in its entirety, and is therefore completely human. While He is fully God and fully human, He is not two distinct beings, but completely one. Finally, Christianity teaches that God, who is Life itself and the Source of all life, can never die; yet Christ, who is fully God, died on the cross and remained dead for three days. God is thus both three and one, both two and one, and was both dead and alive, all of which clearly seem to violate the principle of noncontradiction. How, then, can one remain a Christian and still hold to these principles of rationality?

The first step is to recognize that God, being infinite, is far greater than our limited minds can comprehend. God, as Clarke argues, must be qualitatively infinite if He is the prime Creator of all things, since no finite being can have within itself the sufficient reason why it should possess this limited mode of perfection and not some other. If it did, it would have to preexist itself to select its own particular limitations, which is absurd. Thus, only an infinite being can be the self-sufficient Creator of being. It is understandable, then, that our limited minds cannot comprehend the entirety of God's infinity, but can only view a small part of His rational mind as finitely revealed through creation. There must be some aspect of God's mind which, while incomprehensible to us, is still intelligible in itself and known by God. C.S. Lewis sums it up well in That Hideous Strength:

The laws of the universe are never broken. Your mistake is to think that the little regularities we have observed on one planet for a few hundred years are the real unbreakable laws; whereas they are only the remote results which the true laws bring about more often than not; as a kind of accident.

This is a good start, but it is not enough.

As a stand-alone argument, many will see this as something akin to a "God of the gaps" fallacy. It is lazy to take any and all apparent difficulties in Christian doctrine and explain them away by saying "God works in mysterious ways." Furthermore, it is not a complete answer even within Christianity. Aquinas argues that something that is both asserted and denied, or both exists and does not exist, cannot be the product of any real agent's action, including God's. An agent must exist in order to produce a real effect, and the effect must in some way reflect the agent, since the agent is its origin; thus, the product of the agent's action must always be some sort of existence.

But what is simultaneously affirmed and denied can neither exist nor not exist, since existence excludes non-existence and vice versa. Thus, it cannot be the product of any real agent's actions. Therefore even our infinite God cannot create an absolute contradiction. It does not impose a limitation on Him to say so, since complete contradictions lie outside the realm of being. However, it does appear to preclude the aforementioned Christian doctrines.

How then can these doctrines be true if they are incompatible with the principles of noncontradiction and sufficient reason? Can we in fact show them to be compatible?

Let us deal first with the principle of sufficient reason. Since math is the purest, most abstract form of rationality, we can potentially use its principles to form an analogy for rationality in the order of real being. In math, even though the order of addition usually does not matter (e.g. 3 + 4 = 4 + 3), there exist some infinite series of numbers whose sums can be different depending on the arrangement of their elements. A classic example of this is Grandi's series, 1 - 1 + 1 - 1 + 1 - 1 +… repeating infinitely. The first obvious way to add this up is to group the terms together like so:

(1 - 1) + (1 - 1) + (1 - 1) + … = 0

However, these can be grouped differently with the same method to get a conflicting result:

1 + (-1 + 1) + (-1 + 1) + (-1 + 1) + … = 1

The exact same series of numbers seems to equal both 1 and 0, dependent only upon the grouping of those numbers. We can get even more strange results if we rearrange the series further. If we flip around the (-1 + 1)'s to get (1 - 1), we now have 1 + 1 - 1 + 1 - 1 + … unto infinity. This can be grouped either as

1 + (1 - 1) + (1 - 1) + (1 - 1) +… = 1

or

1 + 1 + (-1 + 1) + (-1 + 1) + … = 2

Repeating the same process of flipping the -1's and 1's, we get 1 + 1 + 1 - 1 + 1 - 1 + … infinitely. This can be grouped either as

1 + 1 + (1 - 1) + (1 - 1) + (1 - 1) +… = 2

or

1 + 1 + 1 + (-1 + 1) + (-1 + 1) + … = 3

Therefore, we have an infinite series which, when added according to normal logical rules of mathematics, can equal either 0, 1, 2, or 3 depending on the order. It is the same infinite series every time, containing the exact same elements, but the sum is different when rearranged.

While it is improper to reduce God to a mathematical formula, we can use this infinite series as an analogy for God's infinite being. Aristotle compares substances to numbers, since just as when any part is added to or subtracted from a number, it becomes a different number, likewise if anything is added to or removed from the definition of a given substance, it becomes a different substance. If one can reasonably compare finite substances to finite sums of numbers, it seems reasonable also to compare God's infinite substance to an infinite sum of numbers. Even though one might point out a difference between a quantitative infinite and a qualitative infinite, there is still some mark by which they both are called "infinite," and thus the analogy can still hold.

When working with finite sums of numbers only, we cannot rationally create a situation where the same sum equals two different numbers. However, the sum of an infinite series shows itself to be sufficient to equal multiple different values while still following normal rational principles. Thus, by analogy, we can accept that God has within Himself the sufficient reason for Him to be three persons in one Godhead (God = both 1 and 3), for Christ to be both fully human and fully divine and at the same time completely one (God = both 2 and 1), and for Christ to be both the never-dying source of life and at the same time to die and be buried (God = both 1 and 0). While we can talk about infinite series and perform rational math operations on them, we cannot picture what an actually infinite series of numbers would look like. Thus, it is understandable that God's infinity, even when following the same normal rules of reason, would still be mysterious to our limited minds, and that these results of 1 = 3, 2, and 0, while incomprehensible to us, are still rational to God.

We must also demonstrate that these doctrines are compatible with the principle of noncontradiction. Perhaps the best answer is that the law of noncontradiction applies only to finite beings and not to the infinite. We have never said that 1, 2, 3, or 0 equal each other in themselves, but that Grandi's infinite series simultaneously equals 1, 2, 3, and 0. Similarly, we have said not that God can create finite beings that defy the law of non-contradiction, but that He is not in Himself subject to it. Still, one may object that this is a cop-out. If we are to deny the applicability of this law in one instance, what is to stop us from arbitrarily doing the same any other time it is convenient? To do so here is therefore a dishonest trick that risks undermining the intelligibility of being. This solution, however, is not merely arbitrary, but relates directly to the idea of form as limitation.

Aristotle's aforementioned comparison between substance and numbers holds because both of them are limited. It is by virtue of adding or subtracting 1 that a finite number becomes different, and by virtue of which it cannot equal the same number as before. Similarly, it is by virtue of adding or subtracting some perfection or mode of being from some substance that it becomes a different kind of substance, and cannot be the same one as before. In other words, it is finitude that restricts beings to the law of noncontradiction.

However, being infinite, it is God's nature to not be limited in this manner. As we have seen, adding or subtracting 1 from Grandi's series gets a result that is no different from the original. The same effect could be achieved simply by rearranging the 1's and -1's, and the result could be rearranged back to the original. Adding or subtracting 1 thus results in the exact same series as before. It is by virtue of adding or subtracting 1 that a given finite number is different from other finite numbers; yet this principle does not hold for Grandi's series.

Similarly, nothing can be added to or subtracted from God's infinite substance that can change it. What would normally change the being of a finite substance does no such thing to God. Because addition and subtraction do not have the same bearing on God as they do on finite substances, and because it is by virtue of addition and subtraction that finite substances are subject to the law of noncontradiction, the principle does not have the same bearing on God's infinite being as it does on finite beings.

We have not proven here that God is indeed a Triune Godhead, that Christ is both God and man, or that Christ died on the cross. These truths come to us from divine revelation passed down through Holy Tradition, and there might exist no other way for us to discover them. But we have shown that the doctrines of faith are not in themselves contradictory to the principles of reason as we know them (and additionally, that reason itself is more mysterious than we modern thinkers would like to admit). The sum of an infinite series such as Grandi's series is able to equal 1, 2, 3, and 0 depending only on the arrangement of the elements therein.

By analogy, God, being infinite, has within Himself the sufficient cause for Him to be at once 1 and 3, 1 and 2, and dead and alive. Because limitation is what requires a being to be subject to the law of noncontradiction, this law need not apply to our unlimited God. Because our limited minds cannot picture infinity in its entirety, it is still a mystery to us just how God can be simultaneously 1, 2, 3, and 0; we have thus not run the risk of reducing God to a rationalistic formula in this process.

At the same time, we have seen a glimpse of the fact that it is indeed intelligible in itself that He should be simultaneously Three and One, Two and One, dead and alive.