Leviathan: A Chaotic Monstrosity of the Sea

Introduction

One of the most darling and devastating creatures of the Old Testament is Leviathan. He is mentioned more than six times by different names and a number of times without a name. Leviathan is depicted as an ultra powerful sea serpent of some sort. The creature is often almost mentioned along with his sidekick Behemoth, who resembles what we refer to as a hippopotamus today but has some distinct features that probably make the referent unknown. [1] This brief paper examines several mentions of Leviathan in the Old Testament to draw out the theological relevance he has to a Christian ontology and the practical relevance he has to the daily life of the Christian. [2]

A Hermeneutical Outline: The Pauline Method

Throughout this essay, I implicitly make use of a three-level hermeneutical method when reading Scripture. There is a historical, allegorical, and spiritual reading of the Bible. The meaning of every Biblical text should be understood with these three levels of the text in mind. This method stems from Origen of Alexandria and was very inspired by St Paul’s statement “The letter kills but the spirit gives life” (2 Cor 3:6). Being heavily inspired by the Old Testament Wisdom literature, Paul believed that one should always look beyond the literal meaning of the text and towards a deeper meaning that may not be apparent at first. This hermeneutic went on to also inspire St Gregory Nazianzus, St Gregory of Nyssa, St Maximus the Confessor, St John of Damascus, Sergius Bulgakov, and others. Nyssa writes, “If we come to a halt at the [Old Testament] for its bare events, [this] does not provide us with the exemplars of a good way of life." [3] Nyssa is clear that we must adopt the teachings and events of the Old Testament to our lives and view them in a much fuller sense that goes beyond the text itself. In the relevant context, the existence of Leviathan is not only a historical claim in the Bible, which would be quite boring by itself, but an allegory for the enemies that threaten us all and a spiritual articulation of something that lurks in the darkness of creation and cannot be explained away with normal conceptual categories of thought. But more on that later.

Leviathan Before the Bible: Great Battles of ‘Ol

Before Leviathan made his way into the pages of the Old Testament as God’s greatest enemy, he fought Baal the Canaanite storm god. Several ancient Ugaritic texts mention Leviathan and ally him with Sea—a manifestation of the ocean as a god himself —that is pitted against Baal. [4] Scholars debate the process of how the Leviathan battle-narrative was compartmentalized into the themes seen in the Old Testament.

To avoid a drawn-out review of the literature, a broad statement can be given to explain this process: Earlier scribes that were closer to the theological and cultural origin of the Canaanite religion that compiled Leviathan narratives were more likely to keep explicit mentions to the god Sea in the Biblical texts. Over time, the god Sea slipped out of the Biblical narrative and his motifs were monopolized entirely by Leviathan. There are some remnants that remain of this earlier tradition—especially seen in places like Habakkuk 3:15 which mentions Sea and not Leviathan—but overall there seems to be a committed effort of later scribes to erase the personalization of sea altogether, that is, erase the god Sea from the Biblical narrative.

In editing Sea out of the Biblical narrative, scribes were keen to replace “Baal” as the opponent to Leviathan with “Yahweh” as the opponent to Leviathan. But this was not simply a 1:1 swap as these substitutions sometimes are between Baal and Yahweh in the Old Testament. In the Biblical narrative, God’s power is much more emphasized compared to Baal’s power in the Ugaritic texts. A thematic comparison between Psalm 104:7-8 and the narrative of its sister Ugaritic text is a mighty fine example of this. [5] Examining this and other texts, paints the picture that God has total power over Leviathan. In short, the Biblical narrative serves to correct the record left by pagan myths. It does this in two ways: (i) Compared to the Ugaritic texts, the Biblical narrative portrays a much more developed theology of transcendence in relation to God. (ii) In every mention of Leviathan, the sea serpent is an enemy of God who can only be controlled and defeated by Him.

Leviathan as a Meal: A Hungry People and a Helpful God

Psalm 74:12-16 reads, For God is my King from old, Working salvation in the midst of the earth. You divided the sea by Your strength; You broke the heads of the sea serpents in the waters. You broke the heads of Leviathan in pieces, And gave him as food to the desert-dwelling creatures inhabiting the wilderness, You broke open the fountain and the flood; You dried up mighty rivers. The day is Yours, the night also is Yours.

In an essay earlier this year, I explained how the Biblical symbol for chaos was often the sea itself. The sea was mysterious, unnavigable, and could not be controlled by humans. The waves would thrash against ships and none would prevail against them. When God the Father divides the sea in Exodus and when Jesus later declares that He can make the sea stand still, the hearer/reader was supposed to come away amazed and bewildered. The power of God is so immeasurably great that He can divide the sea, that is, chaos, at will. The same follows in the case of Psalm 74. If He has powers over the sea, He must necessarily have powers over the heavenly bodies like the sun and moon. The day, night, and all the waters on the earth and above the earth belong to God.

The power of God extends far beyond just the ability to order chaos. He is even able to order and destroy the machinations of chaos. This is where Leviathan comes in. Leviathan is the primetime example of a beast that chaotic elements form when left unchecked by God. Regardless of his origin story, of which we know practically nothing about, Psalm 74 informs us precisely what happens to this creature. God rips through Leviathan like scissors rip through a piece of paper. He destroys the multi-headed beast but He does not stop there. God goes on to engage in a humiliation ritual towards Leviathan. He serves up Leviathan on a platter to His people so that they may feed off it. A body that was once put towards wanton destruction is now put towards fruitful nourishment.

This should be given a deeper meaning than the text alone can provide. The body of Leviathan is not just given to any people but to a certain people. The desert-dwelling creatures refers to all the beings who feasted on Leviathan after God’s victory over the monster. The people (animals too?) feasting on Leviathan were spoken of in tandem to their identity of being desert-dwellers. The desert is another symbolic term we see throughout the Scriptures. In Exodus 16, the desert is the biome the Israelites wandered around in for forty years after being freed from Egyptian slavery by Moses. In Matthew 4, Jesus spent forty days in the desert and the devil tried to tempt Him many times during this period. Like the sea, the desert was also seen as the land of the unknown. It was a dry patch, disassociated from civilization, and was routinely seen as a place for wandering. From the sea to the desert, Leviathan remains entrapped in chaos but unlike the former where the chaos was of his own decision, the latter entrapment in chaos was at the whim of God. The chaotic realm of the sea could not protect Leviathan anymore from the fate that awaited him.

Leviathan was specifically given to desert-dwelling people for a reason. The people were wanderers, perhaps from distant lands, who were hungry and in need of spiritual and material fulfillment. God provided precisely that fulfillment. Feasting on Leviathan’s body was not just nutritionally beneficial but spiritually beneficial as well. God ended the material hunger and spiritual hunger of these wanderers. These were wanderers who did not know God and did not know the Goodness He provides to all. God showed them precisely this Goodness, through nourishing their bodies, which brought them to both a material and spiritual well-being. One can only assume that all the creatures began to erupt in a show of praise and glory to God. Surely, it could be said that the desert rejoiced at this moment (Isa 35). After all, if I was starving and given a hearty meal by an omnipotent deity I sure would have.

The Folly of Modern Scholars: Leviathan Is Inarticulate

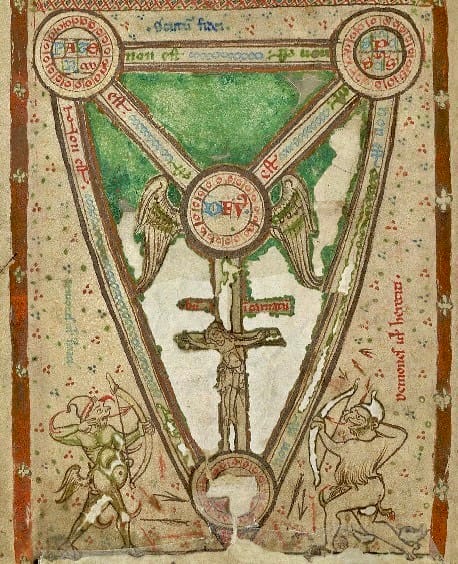

The multiple-headed body of the Leviathan, described further in Job 42 as having a chest hard as a rock, who breathed fire, and whose mouth contains teeth “all around,” is hardly an image that fits our normal conceptual categories of thought. And it isn't meant to be. The Leviathan is the embodiment (literally, its body) of chaos. This is why the Leviathan’s description is so “mythological” in the colloquial use of the word. The Leviathan is the embodiment of chaotic concepts that elude our normal categories of thought. The critical scholar Esther J. Hamori remarks that if you asked a classroom of students to draw what the Leviathan looks like, particularly what it means for teeth to be “all around” the mouth, every picture would be different and none would resemble any known sea creatures. [6] She uses this hypothetical to poke-fun at the idiosyncratic description given of Leviathan by the scribe.

Like many modern scholars who comment on Leviathan’s description, she misses the whole point here. The failure of anyone to depict Leviathan in a coherent fashion is not due to the stupidity of ancient people which prevented them from formulating a coherent description of the creature. The failure she perceives on behalf of the ancient scribe is dialectically a demonstration of the scribe’s great success at portraying chaos itself. By this, I mean that the scribe seemingly fails to explain the outer characteristics of this creature, when in reality the inverse is true: The failure of the scribe and readers to coherently articulate the description of Leviathan speaks to the success of the scribe’s portrayal. The creature cannot be depicted just as chaos cannot be depicted. Leviathan just is. Chaos just is.

For Hamori and others, this is a hard bullet to bite. Influenced by the standards of nineteenth-century German historiography, modern scholars often assume that descriptions in ancient texts are meant to portray an image that can then be conceptualized by a reader. This way of thinking comes about through the presupposition of an empiricist epistemology. Since they accept the Humean framework that all mental images must first come from the existence of the image in the material world, modern scholars assume that for any description given in an ancient text, it must be possible to trace back each and every element to an object in the material world. Once every element of the description is traced back to an object in the material world, these traced-back mental images of objects can be brought together with one another. The result of this process of bringing together all these mental images forms the mental image the author is attempting to articulate with a description.

For instance, let’s use Hamori’s example. Nobody doubts that we can locate “teeth” in the material world, such as in a person or animal’s mouth. Nobody doubts that we can locate something which is said to be “all around” something in the material world, such as a blanket that is “all around” the body of a sleeping person. According to the modern scholar, plugging these mental images together should lead us to a mental image of what the scribe means when he describes Leviathan with “teeth all around.” But there is no coherent image created. The modern scholar concludes, then, that the scribe is too obtuse and naive to have realized this.

From the Christian perspective, the modern scholar is off to a bad start from the beginning. Their methodology presupposes that the only basis for knowledge is through sense-perception of the material world. This omits the factor that all humans feel which is the serious pull towards chaos and disorder that pervades the cosmos. The scribe can tell, however faint a sense at this point in Jewish history, that the cosmos is in a fallen state. In trying to format how precisely to articulate this chaos, the scribe comes up with an entity who lives in the mysterious sea, who typifies the great fear he has towards chaos. The scribe knows this isn't a proper visual of chaos because that itself is impossible. The scribe declares success in the fact that there is no proper visual of chaos. Chaos has an infinite number of machinations it takes. The modern scholar is rarely able to account for this.

Leviathan in Eschatology: God’s Inevitable Victory

God’s defeat of Leviathan is an echo to His ongoing defeat of chaos. God wielded chaos to His advantage, showing everyone that chaos is merely a blip of nothingness in the cosmos, and it can be rooted out at His will. Chaos will one day cease to be. The dark depths of the sea which house Leviathan will someday even meet their match. There will come a time when God will slaughter Leviathan definitively (Isa 27). After all, He created Leviathan as a creature to be played with until He eventually gets tired of him (Ps 104). [7] Leviathan shall be no more, a narrative which is mirrored by the Dragon’s fate in Revelation. [8] Order will prevail, as God will be all in all (1 Cor 15:28). Or according to St Gregory of Nyssa, one can adopt the psalmist depiction from Psalm 150 which pictures the same eschatological reality. He writes, “All will become one body, and one spirit, through one hope to which they were called.” [9] For Gregory, the psalms form a coherent narrative and the 150th psalm is a prophecy of the eschaton where beauty and glory will be given to all “breathing things" (150:6). Whether you prefer the Pauline or psalmist depiction of the eschaton, the conclusion remains: Order will be absolute and chaos will cease in all its current presence. If it even needs to be said, there is no room for eternal damnation here. The chaotic manumission of wills that all desire different things will no longer be a problem at some point. All will be united to God because all wills will desire God alone. That is to say, all beings will be in Paradise.

Our Daily Leviathan: The Chaotic Heads of Dread

We are in the messianic age where God is not yet all in all. Everyday the grimy grip of chaos seeks to rip us away from pursuing a life where God is at the center. Origen offers some words of encouragement in what was, probably, his last written text before he died: “Whenever you are schemed against by an adverse power, pray, and, when you pray, you will be helped, becoming worthy of God’s logos crushing the head of the serpent in you.” [10] In Origen’s reading, the many heads of the serpent are the many forms that sin and evil can take in our life. This is an unsurprising way to read the text for anyone versed in patristics, many Fathers strip the Hebrew Scriptures of their “literal” overtone so as to apply them to our spiritual life. It is not clear if Origen believes there exists a sea monster somewhere far away in the deep blue but I can only surmise he holds on to the literal connotation of the text as well; that is, a connotation which notes the “mere happening” of historical events. [11]

Greed is a head, cowardice is a head, pride is a head. Although Origen does not say this, pride is itself the central head of the serpent. Pride is the source of all sin since all sin comes about through distorting the Trinitarian relational nature of reality. Sin occurs when the person does not take into account that all their actions in the world are done in relation to others and to God. This forms a Trinitarian structure of reality: Self-God-Other. Every action from an individual takes part in God and the other. Sin distorts this in the human psyche by confusing the members of the relational process. Sometimes the other is not taken into account, as in the case of sins like adultery, violence, etc. Sometimes God is not taken into account, as in the case of sins like blasphemy. In all cases, the relational process is disjointed and the self becomes the sole focus of desire. This is why pride is the central head of the serpent. The avoidance of sin is not due to a legalistic injunction—a deontological law for instance—sin is avoided because it disrupts the process of one becoming united with God. It debases the person’s potential for union by instilling pride in the soul. Prayer to God, with of course intercession from the Theotokos and the saints, is our only way of overcoming the multi-headed serpent.

Briefly, this is why an Orthodox baptismal prayer sings in wondrous praise about the defeat of Leviathan.“You hallowed the streams of the Jordan, sending down the Heavens your Holy Spirit, and crushed the heads of the dragons that lurked therein.” [12] I take it that this serves two purposes: (i) It connects the story of Jesus walking on water to the Leviathan narrative. Jesus walking on water displays the sheer omnipotence and omnipresence that God has over chaos and all the forces that chaos wields. Chaos is quite literally put “under His feet,” which echoes the eschatological promise given by St Paul in 1 Corinthians 15:27 and other places. (ii) More relevantly, it connects the slaying of Leviathan to the slaying of our passions and tribulations that baptism bestows unto us. Baptism is an ontological regeneration, as one is brought into the mystical body of Christ. Being brought into the Church and maintaining a devoted prayer schedule is our temporary buffer in the messianic age to fend off the forces of destruction. There will come a time, not in this age but the next, where unceasing devotion is the state-of-being that all glorified spiritual bodies persist in for all eternity. The chaotic heads of dread will be defeated.

The Existence and Ex-sistence of the Leviathan

Since Leviathan cannot be depicted coherently yet the narrative I have painted about it does strike at a spiritual truth that underlies creation, namely that chaos is a metaphysical reality that must be and will be dealt with, it may be better to rephrase the existence of Leviathan as an ex-sistence of Leviathan. The concept of ex-sistence comes from the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan. Lacan, a typically apophatic thinker in his late seminars, defines ex-sistence as a state-of-being for something that cannot be determined by signifier and thus is not able to be articulated. Taken literally, ex-sistence means to “stand outside of” which draws from Martin Heidegger’s use of the term. [13] For Lacan, the signifier is that which represents a subject for another subject. To use Hamori’s example once more, Leviathan was said to have teeth “all around” the mouth. The signifier “all around” is supposed to be signified by “the mouth,” yet because we have no idea what this looks like, recall the classroom hypothetical mentioned earlier, there is a failure in signification. As said before, an accurate description of the Leviathan’s body is purposefully inarticulate.

But while Lacan would like to juxtapose “existence” and “ex-sistence”—the former being everything recognized by the symbolic order of language and the latter being everything that language cannot articulate, which he does since he holds a materialist worldview—I do not accept his ontological presuppositions. There are things that exist, that is, have causal efficacy, spatial properties, etc., and yet are not able to be articulated by language. Leviathan, then, cannot solely be seen as “just” a symbol. And to speak with the word “just” in reference to symbols is incoherent anyways. Etymologically, the English symbol comes from “throwing things together” [sýmbolos] in Greek. A symbol throws together the outward sign of something, such as the image of the Leviathan creature, and the interior meaning of something, such as it being the encapsulation of chaos.

While many moderns like to contrast the two, “this” is a symbol for what “that” reality really is, this is not the ancient meaning of the term. A symbol is not “just” a symbol, a symbol conveys the outer mark and that mark motions to the core of a deeper meaning. Knowing this, allows us to see why existence and ek-sistence cannot be juxtaposed and why the Leviathan is not “just” a symbol in the English use of the term. The existence of Leviathan is denoted by the symbolic language used to describe its ex-sistence, which can never quite signify its existence (the symbolic order fails it), but nonetheless points in the direction of Leviathan’s existence. Thus, Leviathan is the totality of all the fears of the sea wrapped into one entity: Fear of the sea becomes a burgeoning lifeform.

Conclusion

All of us are familiar with chaos in our daily lives. It tugs at our heart strings and consistently seeks to take us off the path of theosis, that is, becoming united with God. Leviathan is a primordial archetype of cosmic chaos. In the Ugaritic texts, his devastating power is unable to be contained by a mere god like Baal, only in the Biblical texts do we see the true narrative of what the earlier texts failed to indicate: God has sovereignty over all, even a great foe like Leviathan. God has sovereignty over chaos. The encounter with chaos is an ever present reality but our encounter with God is an ever present reality too. Unfortunately, many today are more likely to embrace the encounter with the former than the latter. Christians are called upon to bring more people into an encounter with the latter, which is fundamentally opposed to the former, as chaos is opposed to order. Order will prevail some day, but for now, the best we can do is hope and look towards the paradoxical nature of the parousia: God is always-already all in all but He is not yet all in all.

Footnotes

[1] See Nicholas Ansell, Playing with Leviathan: Interpretation and Reception of Monsters from the Biblical World, ed. Koert Bekkum et al. (Boston: Brill, 2017), 105–13; for a review of the debate of whether the Behemoth is really just a hippopotamus.

[2] All citations of Scripture are based on the NKJV.

[3] St Gregory of Nyssa, “Preface,” Homilies on the Song of Songs, ed. Gregorio de Nisa and Richard Alfred Norris (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2012).

[4] Richard J. Clifford, Creation Accounts in the Ancient Near East and in the Bible (Washington, D.C.: Catholic Biblical Association, 1994), 194.

[5] Gert Kwakkel, Playing with Leviathan, 86.

[6] Esther J. Hamori, God’s Monsters: Vengeful Spirits, Deadly Angels, Hybrid Creatures, and Divine Hitmen of the Bible (Minneapolis: Broadleaf Books, 2023), 215.

[7] Today scholars debate whether God is said to be “playing with” Leviathan, indicating they are on relatively equal footing, or whether God is said to have created Leviathan to be “played with,” indicating that God is more powerful than Leviathan could ever imagine. See Playing with Leviathan, 82-85 for arguments on both sides. I take it to be very probably true that the text means to say the latter. The Ugaritic texts certainly said the former.

[8] Those who are familiar with the Septuagint, know that the Greek translators of the Hebrew Scriptures rendered serpent as dragon, which led the Jewish-Christian author of Revelation to mention a dragon in several chapters. Typologically, the dragon of Revelation and the serpent of Isaiah is the same creature. Etymologically, dragon and serpent have the same Indo-European root; or rather, “dragon” comes from the root of “serpent” since the concept of it came later.

[9] Morwenna Ludlow, Universal Salvation: Eschatology in the Thought of Gregory of Nyssa and Karl Rahner (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 74.

[10] Origen, Homilies on Psalms 36-38, ed. Michael Heintz (Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 2023), 200.

[11] P. Tzamalikos, Origen: Philosophy of History and Eschatology (Leiden: Brill, 2007). 362.

[12] “The Service of Holy Baptism,” Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America, https://www.goarch.org/-/the-service-of-holy-baptism.

[13] Jacques Lacan, On Feminine Sexuality, the Limits of Love and Knowledge: Book XX, Encore 1972-1973, trans. Jacques-Alain Miller (New York: Norton, 1999), 22.