Why did Jesus die?

Note: this was taken from an informal, online share by David Armstrong and posted with his permission.

The charge nailed above Jesus’s head was “Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews.” Jesus was crucified, a Roman method of execution reserved for seditionists and insurrectionists. Jesus is remembered in all four canonical Gospels as beginning the last week of his life on the back of a donkey entering Jerusalem and being received by crowds of his disciples, followers, and general sympathizers as “Son of David” or he who brings “the kingdom of our father David.”

Most biblical scholars and historians of Jesus’s life conclude, then, that Jesus died primarily because of aspirations for Jewish national independence, summarized in royal messianism, that were projected onto Jesus by the crowds and that Jesus himself may or may not have encouraged, whether he privately believed it or not. (It’s difficult to adjudicate, because on any read of the Gospels, Jesus does not really go around preaching “Hey, I’m the messiah” as a normal part of his message, so if this was part of Jesus’s messaging in his last week, as seems implied by the choice to ride in on a donkey and reference Zech 9:9, then this is a shift in Jesus’s public relations strategy.) The Romans did not crucify Jesus’s followers alongside him, as Paula Fredriksen argues, because Jesus had been operative in Galilee and Judea for three years and had never pitched himself as a violent revolutionary leading a militant movement.

It was the idea of Jesus as king that needed to die, and that needed to die hard, publicly, and conclusively.

If the Jerusalem priests were complicit, as the Gospels say, then it was largely for the pragmatic calculus that Jesus causing or starting a rebellion was not in the best interest of the nation and that Jesus’s death was perhaps necessary as a result. The Synoptic claim that Jesus died for blasphemy, at least on the priests’ part, needs to be carefully parsed: saying that one is the messiah is not blasphemous; saying, as Jesus does in the Synoptics when on trial, that he will appear at God’s right hand as the heavenly Son of Man might be conceived as blasphemous, at least insofar as it seems to be a claim to possess divine authority or status of some kind. But in any event, it is difficult to know how Mark, Matthew, or Luke (who probably wrote in that order) could have reliable information about the private event they describe; they have an implausible schedule for the event, placing it on Passover itself, whereas John has a more plausible timeline, putting Jesus’s betrayal, arrest, and trial the night before Passover; and the Romans who executed Jesus would not have cared about blasphemy anyway.

The real issue for the priestly aristocrats and for the Romans alike is the idea that Jesus might be pitching himself or received as some kind of candidate for the kingship.

Jesus’s crucifixion therefore makes him a martyr for Judaism, dead at the hands of pagan imperial powers just like the Maccabean martyrs before him or the martyrs of the First and Second Jewish Roman-Wars (66-74; 132-136 CE) after him. Putting his death in that stream of history, actually, is very illuminative. Jesus was born sometime between 6 and 4 BCE, when Herod the Great died; at his death, the so-called “Little Revolt” of 4 BCE broke out and was squashed by the Romans while the Herodians were in Rome haggling with Augustus over Herod’s will. In 6 CE, when Jesus was 10-12 years old, Herod Archelaus was deposed as ethnarch of Judea, Samaria, and Idumaea and Judea was made a Roman province; Quirinius, governor of Syria, took a census that included Judea and sparked another revolt led by Judas the Galilean, also summarily crushed by the Romans. The Roman prefects were invariably brutal and mostly incompetent; the most efficient and savage of them was none other than Pontius Pilate, who held the post from 26-36 CE and was widely perceived as outrageous by the Judean populace. Pilate was a murderer with state power, and that both kept him and eventually lost him his job, when his suppression of a Samaritan religious revival (messianic movement?) earned him a recall to Rome in 36, after which we lose track of him. Jesus’s death sometime between 28 and 30 would have been a routine event for him, to which he would hardly have given an afterthought. It is entirely possible that if Pilate later encountered ongoing followers of Jesus in Jerusalem or Judea that he might not even have remembered the man they were talking about.

The death and destruction of the two Jewish-Roman Wars that erupted over Roman abuses of the region and internal Jewish division over how to respond to their imperial overlords is the source of some of the most famous traumas of Jewish history. The destruction of the Temple in 70 CE, the death of the rebels at Masada in 73/74, and the near-genocide carried out by the Romans against the Judean populace during the Bar Kokhba Revolt all but destroyed the Jewish community in Syria-Palestine. It held on, and regrew, but the losses sustained would be legendary. Rabbi Akiva, for example, the most famous sage of the tannaim, was reportedly flayed alive while reciting the Shema in the sight of his weeping students; Rabbi Hananiah ben Trydon was wrapped in a Torah scroll and wet wool and burned alive.

Jesus’s death at Roman hands should be understood in alignment with those other deaths. This is the martyrdom of someone who worked passionately for three years of his adult life to bring about a reformation of his people’s social and economic circumstances and a revival of their religious commitment in view of what he and others believed would be an imminent change in their political fortunes when God intervened to free them. His prophetic announcement was joined to a call for economic redistribution of wealth and reversal of social hierarchies and pointed to the Torah’s radical teachings of love for God and neighbor, just like other Jewish teachers did. Jesus went to the cross for his proclamation of the Kingdom’s message.

Christians believe more about Jesus’s death, of course. Developing the theology of Deutero-Isaiah, Maccabees, and Daniel that the martyrdom of a prophet or wise or righteous person could avert disaster for the nation and atone for sin, Paul develops the idea that Jesus’s death on the cross is a death for sins. Developing the theme of what Jewish scholar Jon Levenson calls the “Death and Resurrection of the Beloved Son” motif from Canaanite, Proto-Israelite, and preexilic Judean religion, too, Jesus’s death is the handing over of God’s beloved, messianic son to the monstrous powers of chaos and Death (Mot in the Ugaritic Baal myth) that was, in those cultures, the etiological rationale behind an active practice of child sacrifice.

The Gospels evolve in their understanding of Jesus’s crucifixion. Written some forty to sixty years after Jesus’s lifetime, they are composed long after the fact of Jesus’s crucifixion has been read backwards into the texts of the Hebrew Bible and Early Jewish literature as an aspect, rather than a counterargument, to Jesus’s messianic identity. The lingering question for New Testament literature generally is not what sense to make of Jesus’s death on the cross but of whether there is more messianic stuff to come afterwards.

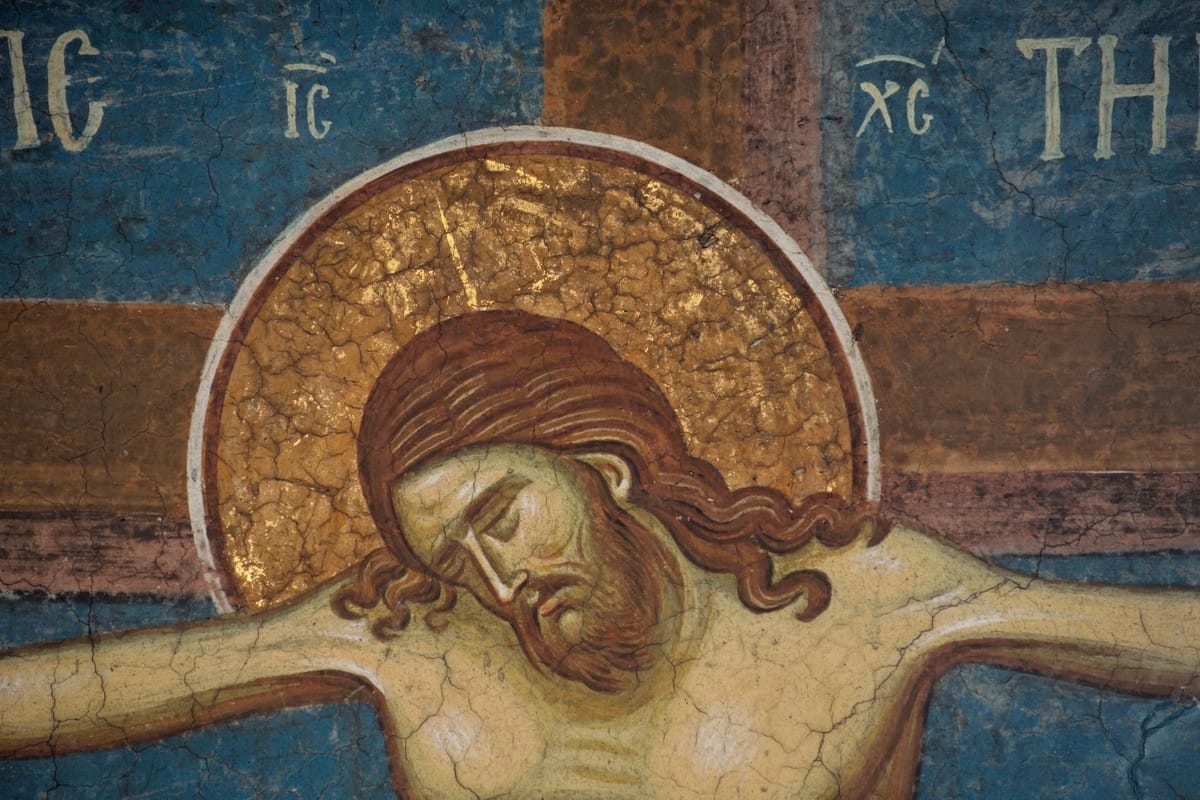

In Mark, dying on the cross is now a part of what it is to be the messiah, at least for Jesus: his only “anointing” in the entire Gospel is for burial (Mk 14:3-9). But this is the same Jesus who gives the Olivet Discourse in Mark 13 about the Son of Man’s future coming in glory: the cross and the burial will lead to resurrection and vindication and swift parousia. So, too, with Matthew; in Luke, the future expectation of Jesus’s coming is indefinitely delayed by the apostolic missions to Jews and gentiles. By the composition of John’s Gospel, though, there is the brilliant move to see the crucifixion of Jesus and the mocking titulus crucis hung above his head as, unintentionally and ironically, the true evangel: Jesus’s hanging on the cross is his parousia, his coming and enthronement in glory.

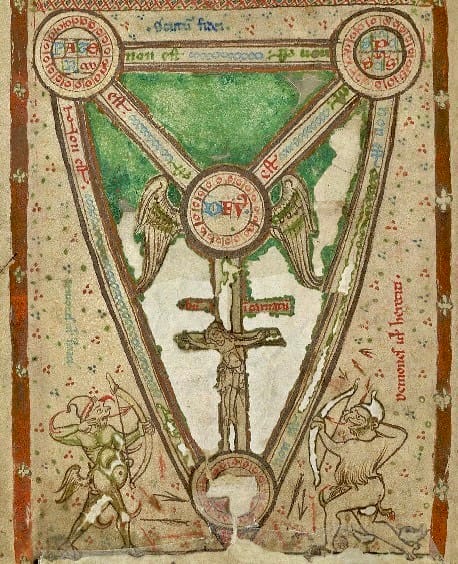

For Early Christians, these different themes would coalesce to become the grounds of various theories of atonement. For patristic writers that emphasize the so-called “ransom” theory of the atonement, Jesus’s death in some sense pays off the claims of the powers of Sin, Death, the Underworld, and the Devil (all themselves recycled from the older monsters of Near Eastern mythology) over Israel and, even more, the gentile nations too. In Melito of Sardis’s Peri Pascha, for example, Jesus is the Paschal Lamb whose blood turns away the Destroyer; in Irenaeus, Jesus’s death is a kind of divine trickery on the Devil to both pay him off and defeat him in one fell swoop. Later Christians would develop more elaborate soteriologies from Jesus’s death, some enchanting–like, for example, the “deification through the cross” that Khaled Anatolios identifies in the Eastern Fathers, or the much less helpful and healthy penal substitution of later Latin theology. But all of these are contextual responses to the fact of Jesus’s death rooted in the contexts of the thinkers themselves, who have to reassemble the meanings of the text in ways that make sense to them.

Today, we are in our own position to make decisions about what Jesus’s death can reasonably mean to us. Three useful summary notes, then. First, Jesus was not killed by “the Jews.” Instead, Jesus was a Jew and died alongside other Jews for the cause of Jewish freedom at Roman hands. Jesus’s idea of what liberation for his nation meant differed from others of his contemporaries, forebears, and many later figures: in an imaginary world where they sat and talked through their differences, for instance, Jesus and Simon Bar Kokhba would have had utterly different ideas about what Jewish independence could or should mean, and both would have dissented from Theodor Herzl or Martin Buber or Abraham Joshua Heschel. But all were Jews agitating for the cause of Jewish liberation, and Jesus, like Rabbi Akiva and many others, suffered and died for that cause.

Second, if as Christians we wish to understand Jesus’s death in theomachic terms, as a form of divine warfare against cosmic powers both impersonal and personal that enslave the human race, like Sin and the Devil, then we should follow the logic of the mythology that informs that way of talking and not attribute the cause of Jesus’s death to God. That is to say, Jesus does not die to pay off God or to appease God. If there is some form of divine wrath that Jesus turns away from Israel, that divine wrath is not the threat of punishment with eternal hell, but is rather a way of talking about the actual circumstances of Judea’s captivity to foreign powers or, apocalyptically, the universe’s captivity to evil deities. In the “death and resurrection of the Beloved Son” motif, Jesus is in the position of Baal, handed over by El to Mot to satisfy the claims of Mot; it just so happens that Baal’s death at Mot’s hands will lead to Mot’s own destruction. If there is something uncomfortable about the idea that Death or the Devil or whoever should have some kind of cosmic claim on anyone that God has to respect, we should acknowledge that part of the reason for that discomfort is that theology evolves over time, and that the way religion recycles mythological and cultic language is not always perfectly consistent with prevailing ideas. As Jews and Christians were gradually progressing towards a more classical theism, where God is understood as coequivocal with ultimate reality and does not compete with other creatures for ontological space, the traditional language of scripture, myth, and worship were still very much that God did in fact share that space and that the space itself was contestable. Because of that, any atonement theology worth its liturgical salt is going to be multilayered, beginning from the observation of Jesus’s historical circumstances that led to his death at the hands of the Romans and proceeding from there through a cycle of interpretations rooted in the experiences and texts of Early Jews and Christians that Christians have found useful and authoritative for understanding the meaning of Jesus’s death. But those interpretations also have to take account of evolving social and cultural contexts. The idea of God giving up his son to death was a cultural metanarrative of parts of the Near East; it’s not really in the modern West other than through its use in Christianity (and its mitigated use in some Jewish ways of thinking through the national suffering of the Jews as a people over time, often in dialogue with Christians), so if it is going to have meaning for us today, it is going to need to be received in terms of our own cultural metanarratives. As the ideals of sacrificial heroism remain poignant for us, however poorly we live up to them, we have many resources to work with both ancient and modern on this front.

Third, we should acknowledge that any and every attempt to personalize the meaning of Jesus’s death–that Jesus died for me, for my sins, etc.–commits us to the logic of the cross as much as it serves as grounds for a relationship with God through Jesus. Here I speak explicitly as a Christian to other Christians. If Jesus died on the cross, among other things, for you and for me, then we, too, are obligated to understand and internalize what the cross means. The cross is a symbol of imperial oppression that has been, for Christians at least, transformed into a symbol of victory and hope. If Jesus died for you and me, then we are obligated to also be willing to suffer and die on behalf of the oppressed. We should not align ourselves with empire or with the forces of oppression. Passovers Jewish and Christian should have the same theme here: God is the liberator, not the enslaver.

And yet, Christians will have to reckon with the fact that the cross IS a frequently oppressive symbol today. For most of Jewish history, for example, and for a not insigficant portion of Muslim history, the cross is a symbol of Roman and Western imperialism every bit as much under Christian usage as it was under pagan usage. Under the banner of the cross, Christians have carried out their own persecutions and warfare against religious and cultural others, sometimes marginalized members of their own communities, sometimes alternative imperial societies with which they feel they are competing for the fate of the world. This remains as true in the 21st century United States as it was in ninth century Byzantium or 13th century Italy. And it is here that the historical circumstances of Jesus’s actual death should be perennially relevant for us. Jesus died as a victim of the state. Even if we understand the cross as, mystically, a “triumphal procession” of the powers in chains (Col 2:15), the force of that interpretation relies exactly on the fact that such was not obvious by any worldly standard. Jesus’s Kingdom is not of this universe, for if it were, his followers would have fought for him (Jn 18:36). If Christians conclude that they must engage in violence for reasons of self or national defense, they minimally should not be confused that this constitutes a real (however necessary) violation of their baptismal participation in the cross and their charge as disciples to take up the cross.

They certainly should not think that they can ever take up the sword in defense or promotion of the Kingdom of God.